Image: Hope Kphé

Published on 08/26/2024

By Roseli Andrion | Agência FAPESP – Brazil accounts for 38% of global coffee production, yet growers face a series of obstacles to preparation of coffee beans for export. One of the problems is quality control, which is done manually. “Pickers separate out the beans that don’t have the specified quality, for whatever reason. Based on this analysis, they decide whether the composition comes within the expected quality scale and whether the process can keep going or should be interrupted and adjusted,” says engineer Carlos Fernando Baltieri, managing partner of Hope Kphé, a startup based in Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo state, Brazil.

Baltieri has worked in the coffee industry for over 30 years and is well aware of the difficulties. Manual evaluation is not one of the operator’s official tasks in production, he explains, but it has to be done to make sure the equipment is correctly adjusted. To assist these workers with coffee sorting, Hope Kphé has created a solution that performs the task automatically. Developed with the support of FAPESP’s Innovative Research in Small Business Program (PIPE), it selects coffee beans on the production line to raise export yield.

“When beans are manually selected, a large proportion of good beans are discarded as unfit for export because the sorter hasn’t been calibrated properly. Sorting and grading before or during selection provides information that the operator can use to adjust the machine so as to increase its efficiency and reduce the amount of misgraded beans, which can be exported instead of being held back for the domestic market,” Baltieri explains.

Coffee exports currently fetch BRL 1,400 per bag, compared with BRL 1,190 per bag for coffee sold on the home market. “If large amounts that should be exported end up being sold on the domestic market, the exporter loses. We want to help minimize these losses. In a medium-sized facility, for example, an improvement of 1% could represent about BRL 150,000 per month,” he says.

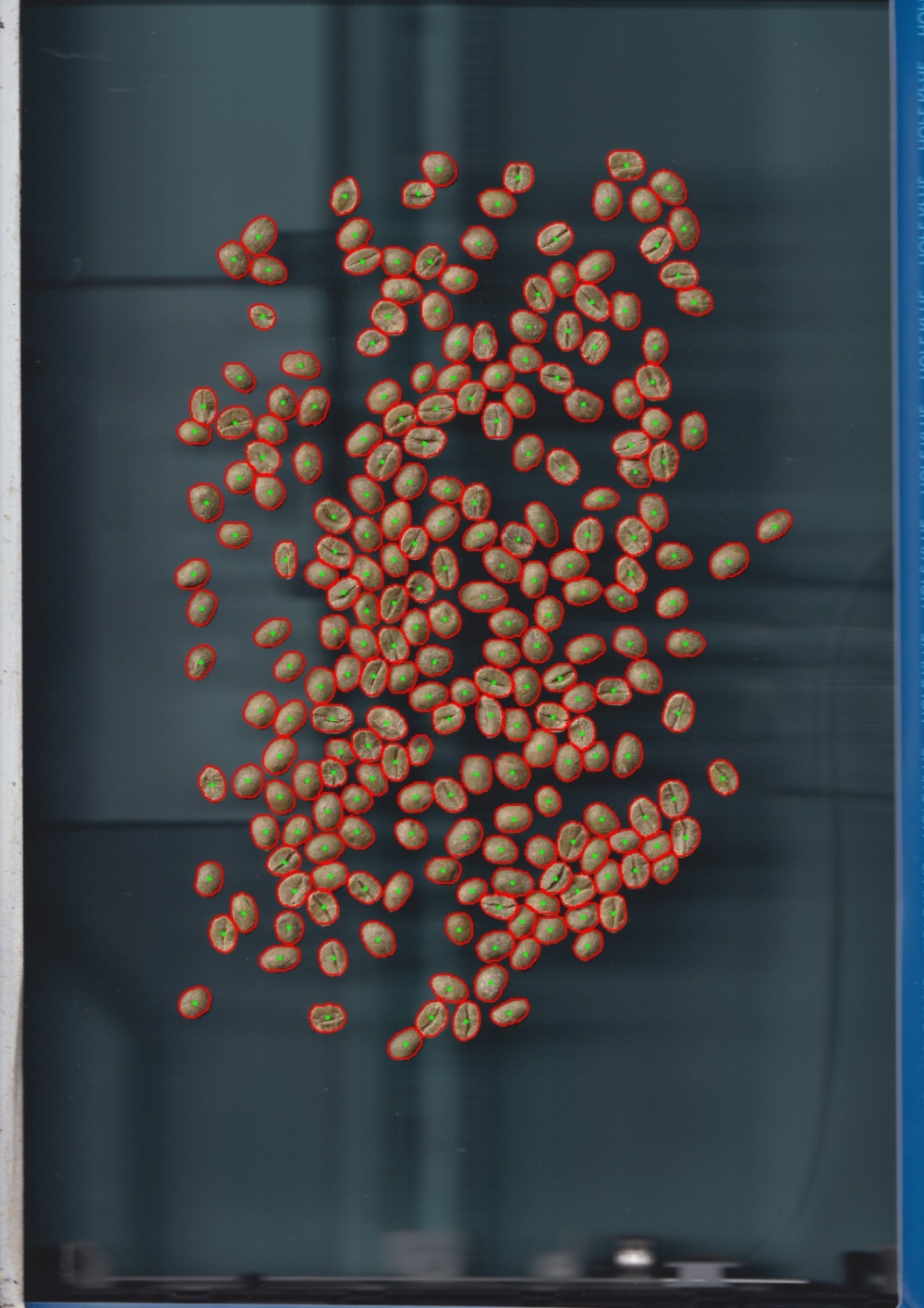

The solution entails scanning the beans (known as cherries when picked) to analyze them in terms of color and shape. “In hand sorting, the operator places them on a leather color chart, but in automatic sorting they’re put in a scanner and the system analyzes both sides to sort them by color. It’s fast, and a great help to the professionals involved,” Baltieri says. “What’s more, management can use the data collected in this process to make more evidence-based decisions and obtain real gains in production.”

Hope Kphé is partnering with the University of São Paulo’s Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture (ESALQ-USP), the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) and a number of coffee traders. Doctoral scholarship awardees are involved in its research at both institutions.

Supply chain traceability

This type of sorting will permit better traceability of coffee throughout the supply chain, Baltieri says, explaining that extracting information from a batch is like furnishing a certificate of origin for the product: “Consumers will be able to track the production process from the coffee grove onward. They’ll know where their coffee comes from.” Later on, small producers will be able to offer consumers the best beans in a micro batch to make a specific blend, for example.

The solution could empower coffee growers. “They’re the weakest link in the chain, as the plantation is directly affected. This analysis will tell them all about the quality of their coffee, whereas as things now stand it’s exporters who lay down the rules. If growers know the value of their coffee, they’ll be in a stronger position to negotiate prices,” Baltieri says.

For Gustavo Valio, his business partner in Hope Kphé, all this matches an existing need. “Specialized professionals are needed in coffee groves. When the harvest comes in, the warehouses have to hire people without any training,” he says. “This system not only helps the warehouses but also lets growers know what they’re holding before they sell and lets exporters know what they’re buying.”

Another important aspect of coffee quality is the sensory property known as palatability, which is also manually assessed. Samples are roasted, ground, prepared and tasted by graders who evaluate their aroma and flavor. “We aim to make this process technological and grade the beverage on the basis of a chemical analysis,” Baltieri says.

Resistance to technology

The 2024 crop was harvested in June and July, offering an opportunity for final testing of the solution, which is expected to be in use at several companies next year. In parallel, the startup is preparing to test the platform on other crops, such as peanuts, soybeans, corn, and common beans. “Peanuts are harvested at the end of January. We aim to do tests on this crop in 2025,” Baltieri says.

“When we have the sequence of steps for selection and grading, it will be easier to include other grains,” Valio notes.

The coffee industry is conservative and reluctant to introduce new technologies, such as cloud data processing or software as a service (SaaS) subscription platforms. Hope Kphé’s system, for example, had to be designed to run locally. “Hopefully it will be cloud-based in future, but right now we want to focus on building trust and confidence in this option,” Baltieri says.

For Valio, the technology may help enhance the accuracy and precision of coffee cherry selection and grading. “With artificial intelligence in the cloud, we can train the system remotely instead of having to run it here in Ribeirão Preto. The same goes for software updates. This is certainly the best option,” he says.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/52586