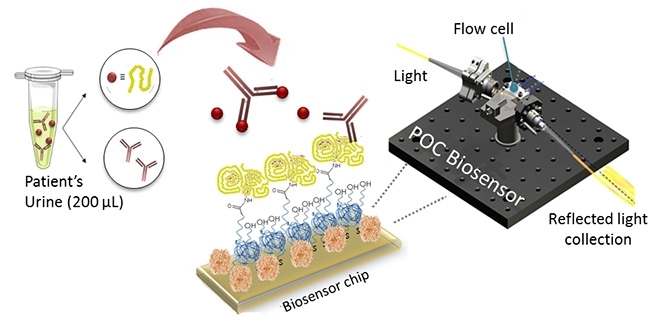

Device developed by Spanish researchers detects the presence of the gluten peptide most resistant to digestion in urine samples. The operation is as simple as that of a drugstore pregnancy test (image: ICN2)

Published on 05/13/2021

By Elton Alisson in São Carlos | Agência FAPESP – People with celiac disease face the challenge of ensuring that their diet is entirely free of gluten, part of the elastic protein found in wheat, rye, barley, and some barley malt. This is a particularly complex challenge not only because gluten is an ingredient of many foods in different forms and proportions but also because even products labeled gluten-free may be cross-contaminated with gluten and trigger reactions in people with celiac disease.

A nanometric optical biosensor developed by researchers at ICN2, the Catalan Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology hosted by the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) in Spain, can help people with celiac disease avoid the unwitting ingestion of gluten.

The simple and highly sensitive point-of-care device analyzes a urine sample in search of one of the main gluten peptides, which it can detect even in tiny amounts if the patient has ingested food containing gluten.

The novel method, which works like a drugstore pregnancy test, was developed by Professor Laura Lechuga and her Nanobiosensors and Bioanalytical Applications Group at ICN2. Lechuga presented the research behind the device during the São Paulo School of Advanced Science on Modern Topics in Biophotonics, held at the University of São Paulo’s São Carlos Physics Institute (IFSC-USP) in Brazil on March 20-29, 2019. The event was supported by FAPESP through its São Paulo Schools of Advanced Science Program (SPSAS).

“The sensor will be particularly useful for monitoring the diet of children with celiac disease whose parents are unable to control what their offspring eat away from home. With just a few drops of urine, the device can rapidly detect whether gluten has been ingested on a given day. If so, the patient can avoid consuming the suspected source again,” Lechuga told Agência FAPESP.

The biosensor is based on the principle of surface plasmon resonance (SPR). SPR can be used to quantify the substance of interest by measuring the refractive index (deviation angle), light absorption and fluorescent properties of the molecule analyzed or of the chemical-to-optical transduction medium (which “translates” the chemical signal into an optical one).

With an optical detector, the device identifies and quantifies α-gliadin 33-mer, the gluten peptide most resistant to breakdown by gastrointestinal enzymes.

“One of the byproducts of gluten metabolism is this peptide that resists digestion and can be detected in the urine and feces,” Lechuga explained.

To evaluate the biosensor’s performance in terms of sensitivity, selectivity and reproducibility, the researchers conducted a study of 44 celiac patients who had followed a gluten-free diet for at least two years. The patients were classified at enrollment as asymptomatic or symptomatic using a questionnaire with a gastrointestinal symptom rating scale, after which 39% were deemed asymptomatic and 15.8% symptomatic. The presence of gluten in their diet was also assessed using a questionnaire on the food ingested during the previous few days. The urine test for α-2-gliadin 33-mer showed 25% with at least one positive result for the peptide. The device was able to detect levels of the peptide as low as 0.33 nanograms per milliliter in urine.

“We found that the biosensor is capable of detecting the inadvertent consumption of gluten by people with celiac disease who’ve followed a gluten-free diet for a long time, whether or not they exhibit symptoms of celiac disease,” Lechuga said.

“Our technique should be considered a promising opportunity to develop point-of-care devices for the efficient, simple and accurate monitoring of a gluten-free diet and therapeutic follow-up of celiac disease patients.”

Partnerships with device manufacturers

Other biosensors developed by Lechuga’s group at ICN2 in Spain are set to come to market via medical device and equipment manufacturers. They include a biosensor designed to monitor the delivery of anticoagulants used by patients with cardiovascular disease or thrombosis.

This SPR device contains gold nanostructures to which specific bioreceptors are attached to detect biomarkers that analyze a small sample of the patient's blood to measure drug dosage. The patient or doctor can then adjust the dose to achieve the optimal effect. If the dose is too low, blood clotting may occur. Too high a dose could cause side effects such as internal bleeding.

“We’re talking to a number of multinationals that are interested in producing and marketing the device, which works like the blood sugar test used by diabetics,” Lechuga said.

“With just a few drops of blood, the biosensor can detect whether the drug dose is sufficient or excessive, so that the drug can be properly administered.”

Other biosensors have been developed by the researchers in recent years for the early detection of lung and ovarian cancer and for the analysis of water contamination.

“One of the advantages of optical biosensors like the ones we’ve developed is that they’re much more sensitive than photonic and electrochemical sensors. They can detect compounds of interest in extremely small samples of materials such as cells,” Lechuga said.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/30491