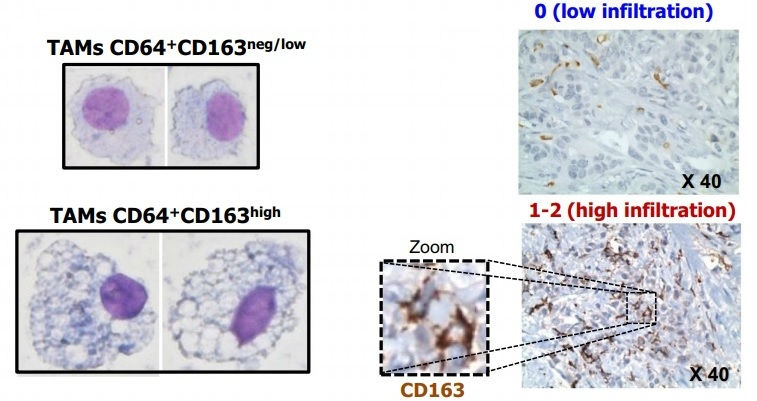

This study shows that patients develop alterations in a type of leukocyte at the initial stage of the disease. This discovery paves the way for the enhanced diagnosis and treatment of this type of tumor (comparative image between different profiles of protein CD163 expression in tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) differentiated from monocytes of breast cancer patients [left]; detailed image showing different levels of TAM infiltration detected in tissue microarray [right] /

Published on 03/23/2021

By Maria Fernanda Ziegler | Agência FAPESP – Immune system cells in the blood of breast cancer patients undergo alterations early in the disease course, according to a study published in the journal Clinical & Translational Immunology.

The authors believe that this discovery may contribute to the early identification of aggressive tumors and help enhance personalized immunotherapy strategies in the future.

The study was conducted while Rodrigo Nalio Ramos was doing a doctoral research internship at Claude Bernard University in Lyon, France, with a scholarship from FAPESP. The principal investigator was Jose Alexandre Marzagão Barbuto, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s Biomedical Sciences Institute (ICB-USP), and the supervisor abroad was Christophe Caux, a senior scientist at the Lyon Cancer Research Center (CRCL).

“It’s probable that monocytes, a type of leukocyte, can be used as a ‘thermometer’ of the disease. At least that’s what we found for breast cancer patients,” Ramos told Agência FAPESP.

Monocytes are the largest blood cells and account for approximately 7% of leukocytes. They are important immune cells, patrolling the body in search of potential threats such as viruses, bacteria and tumor cells. They are produced in the bone marrow and travel in the bloodstream to other tissues where they differentiate into macrophages (cells that engulf and destroy pathogens and apoptotic cells) or dendritic cells (cells that process antigen material and present it on the cell surface to the immune system structures that produce specific antibodies).

In this study, the researchers collected monocytes from the blood of breast cancer patients and tried to differentiate them in the laboratory into pro-inflammatory macrophages, which tell the immune system to send reinforcements to the tumor site. Monocytes were collected from 44 blood samples donated by breast cancer patients treated in France and at Pérola Byington Hospital in Brazil, as well as 25 samples from healthy individuals who served as controls.

“We used a cocktail of cytokines [signaling proteins that modulate the immune system] to try to induce monocytes to differentiate into pro-inflammatory macrophages. In theory, this type of cell is supposed to tell the organism it has a tumor and eliminate it,” Ramos said. “However, the monocytes failed to perform this role in approximately 40% of the patients and displayed a very similar profile to that of the intratumoral macrophages associated with an adverse outcome.”

The researchers then analyzed monocyte gene expression to determine which messenger RNAs the cells were producing. The analysis identified alterations to several signaling pathways, even in patients whose cells differentiated into macrophages like they should in healthy subjects.

“This confirms that breast cancer isn’t just a local disease. It doesn’t affect only the breast but affects all cells systemically. The defense cells are already altered when they enter the bloodstream,” Barbuto told Agência FAPESP.

The researchers cannot yet explain exactly how these tumors interfere with the immune system. “One possibility is the secretion of factors [proteins with a modulating function] into the blood,” Ramos said, “another hypothesis could be a systemic effect via the bone marrow, but this is harder to verify. In this case, the disease could affect monocyte precursor cells.”

According to Ramos, cancer can develop slowly over a period of years. “If we could detect monocyte alteration early on when there are no signs of the disease, it might be possible to prescribe more tests to determine if something is wrong,” he said.

The article “CD163+ tumor-associated macrophage accumulation in breast cancer patients reflects both local differentiation signals and systemic skewing of monocytes” (doi: 10.1002/cti2.1108) by Rodrigo Nalio Ramos, Céline Rodriguez, Margaux Hubert, Maude Ardin, Isabelle Treilleux, Carola H. Ries, Emilie Lavergne, Sylvie Chabaud, Amélie Colombe, Olivier Trédan, Henrique Gomes Guedes, Fábio Laginha, Wilfrid Richer, Eliane Piaggio, Jose Alexandre M. Barbuto, Christophe Caux, Christine Ménétrier-Caux and Nathalie Bendriss-Vermare can be retrieved from onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cti2.1108.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/33142