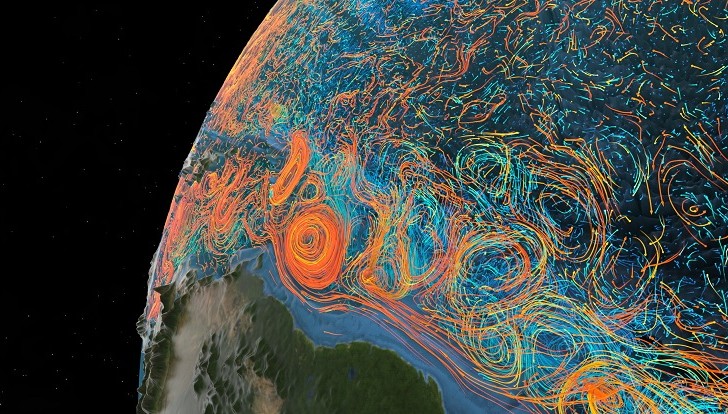

The team brought together scientists from Germany, Switzerland, and Brazil. The most serious effects may occur in the northern Amazon, with a drastic reduction in rainfall (image: CEN/Universität Hamburg)

Published on 11/25/2025

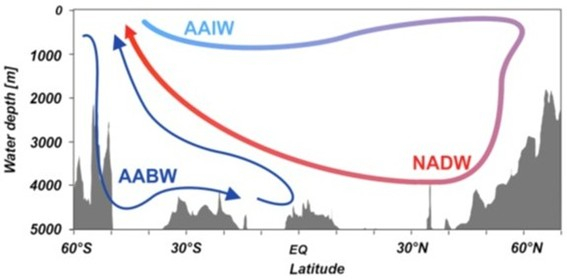

By José Tadeu Arantes | Agência FAPESP – The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is one of the main “engines” of the Earth’s climate. It functions as an oceanic conveyor belt, transporting heat and nutrients and connecting the surface waters of the tropics with the deep waters of the northern region. Changes in this system have always been associated with abrupt changes in the global climate, such as those that occurred during the last ice age.

A new study shows that the AMOC has remained stable over the last 6,500 years after fluctuating during the early Holocene. However, this stability is now under threat. By combining field research data with projections from the most accurate climate models, the study indicates that human-caused changes could lead to a weakening of the circulation that is unprecedented in recent Earth history. The northern Amazon, the most pristine part of the forest, could be severely impacted by a drastic reduction in rainfall.

The results were published in the journal Nature Communications.

The international team that conducted the study included scientists from Germany, Switzerland, and Brazil. The researchers quantitatively reconstructed the intensity of the AMOC throughout the Holocene (the last 12,000 years) using marine sediment samples collected at different points in the North Atlantic and analyses of radioactive elements – thorium-230 and protactinium-231.

“These radioactive elements are constantly produced in the water column from uranium. Since thorium quickly attaches to particles while protactinium circulates longer, the protactinium-to-thorium ratio in the sediments serves as a ‘proxy’ for ocean circulation intensity. Higher values indicate weakening and lower values indicate intensification,” explains Cristiano Mazur Chiessi, a professor at the School of Arts, Sciences, and Humanities at the University of São Paulo (EACH-USP) and co-author of the study.

Schematic representation of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (light blue and red arrows), which transports warm water from south to north near the surface and cold water from north to south at intermediate depths. The drawing also shows another circulation (dark blue arrow) that transports water at great depths (image: sketch by Cristiano Mazur Chiessi based on information from Voigt et al., 2017)

The team used Bern3D to convert the field data on the protactinium-thorium ratio into water flow values. Bern3D is an Earth system model developed at the University of Bern in Switzerland that simulates oceans, the atmosphere, and biogeochemical cycles. This allows sediment records to be converted into quantitative estimates of ocean circulation. This made it possible to estimate the intensity of circulation in Sverdrups (Sv) – 1 Sv is equivalent to 1 billion liters per second.

The results showed that it took about 2,000 years for the AMOC to recover from its weakened state after the end of the last glaciation. Between 9,200 and 8,000 years ago, the AMOC declined further due to the influx of fresh water into the North Atlantic from melting glaciers and glacial lakes, including Lake Agassiz in Canada and the United States. This period included the “8.2 ka event,” which is recorded in Greenland ice cores as one of the most intense cooling episodes of the Holocene. Since 6,500 years ago, however, circulation has stabilized at around 18 Sv. It has maintained this intensity to the present day.

“We’ve reconstructed the advance of deep waters from the North Atlantic toward the South Atlantic over 11,500 years. And in the last 6,500 years, we haven’t detected any major oscillations even remotely close to what’s projected for 2100,” says Chiessi. “The future scenario is very worrying. It must be taken seriously by both governments and civil society, including the scientific community.”

According to Chiessi, the projected weakening will cause changes in rainfall across the planet’s tropical belt, especially in South America and Africa. It will also affect the monsoon system in India and Southeast Asia.

Impact on the Amazon

One of the most significant impacts is expected to occur in the Amazon. “We project a marked decrease in rainfall in the northern Amazon, precisely the most preserved region of the forest. This effect may occur because equatorial rains will tend to shift southward with the weakening of the Atlantic circulation. As a result, the northern Amazon, covering areas of Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, and the Guianas, may face significant reductions in rainfall,” Chiessi predicts.

The researcher emphasizes that this scenario is even more severe because it involves the forest’s most well-preserved area. Unlike the southern and eastern regions of the Amazon, where deforestation and degradation have advanced significantly, the northern region has served as a “safe haven” for biodiversity. “It’s precisely in this region, which has been less impacted until now, that climate change could create new and dramatic vulnerabilities,” he notes.

Collection of a sediment column from the bottom of the Labrador Sea in the North Atlantic between Canada and Greenland. The sediment column collected at this location served as the basis for the scientific article (photo: Stefan Mulitza)

A previous study published in 2024 by Thomas Kenji Akabane and collaborators, including Chiessi himself, had already warned of this possibility. In this study, the scientists used pollen and microscopic carbon records in marine sediments to show that past weakening of the AMOC led to the expansion of seasonal vegetation at the expense of the northern Amazon rainforests. Models indicate that similar future weakening would produce greater impacts, exacerbated by deforestation and burning in other parts of the basin.

Tipping point?

The cooling of the AMOC could represent a tipping point in the global climate system. If the projections are confirmed, there will be an unprecedented disruption in the ocean circulation that sustains the planet’s climate balance. Specialized researchers agree that weakening is a clear trend. However, the data do not yet allow us to determine whether it is already occurring. “Direct monitoring only began in 2004, and the ocean responds more slowly than the atmosphere. Therefore, the records are still insufficient for a conclusive answer. However, despite this uncertainty, the urgency to act is non-negotiable. There’s still time, but our actions must be robust, rapid, and comprehensive, involving governments and civil society,” Chiessi warns.

Both studies were supported by FAPESP through projects 18/15123-4, 19/19948-0, and 21/13129-8.

The article “Low variability of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation throughout the Holocene” can be read at www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-61793-z.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/56589