Researcher Angela Zanata looks for fish while collecting in a creek on the Jauaperi River (photo: André Julião/Agência FAPESP)

Published on 06/06/2024

By André Julião, from Rorainópolis (Roraima) | Agência FAPESP – The mystery continues. The places where researcher Tyson Roberts is said to have collected the only four known specimens of Iracema caiana were intensively searched by the DEGy Negro River Expedition team, which traveled to this location, as well as a part of the Jauaperi River, to collect electric fish, better known as poraquês and sarapós.

After three days and more than 60 species collected, including 15 sarapós, the team ended the search on the Jauaperi River. The vessel Comandante Gomes spent one night in the community of Tanauaú and two nights in Itaquera, a community in the municipality of Rorainópolis, in Roraima state. In addition to the temporary change of river, the team also temporarily changed states.

“We visited the same places indicated by Tyson Roberts where he supposedly collected Iracema caiana. We collected dozens of species from different families, including sarapós, but we ended this part of the trip without finding this enigmatic species of electric fish,” explains Osvaldo Oyakawa, a research support technician at the Museum of Zoology of the University of São Paulo (MZ-USP), who coordinated the expedition.

The DEGy Negro River Expedition was part of the “Diversity and Evolution of Gymnotiformes (DEGy)” project, supported by FAPESP. The reports make up the Field Diary – Negro River series (see all the episodes at: agencia.fapesp.br/en/field-diary).

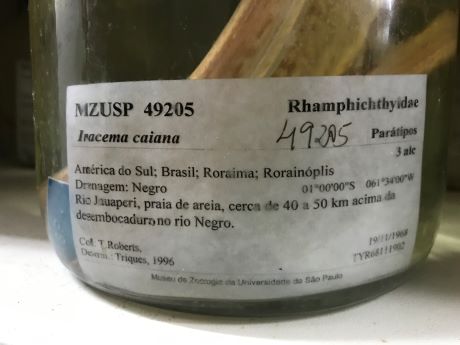

“The rarity of Iracema specimens available for study in scientific collections makes it difficult to establish more precise relationships with other species of the electric fish order. Hence the effort to obtain more specimens from their still unknown natural environment,” explains Naércio Menezes, professor at MZ-USP and coordinator of the project.

One of the four Iracema caiana specimens deposited at the USP Museum of Zoology in 1968. No other specimens have been collected since then (photo: Thiago Loboda/MZ-USP)

Agência FAPESP searched for information in Itaquera about a possible visit by Roberts in 1968, but was unsuccessful. By e-mail, the researcher, who is still active at the age of 84, says he doesn’t remember the details of the collection, which took place in his early career.

“Many people helped me collect fish specimens, usually local fishermen whose names I didn’t get. If I had regular helpers who accompanied me on long trips, they couldn’t have been from there [Itaquera], and they wouldn’t remember the collections they helped me make in different places. I’m sorry I can’t provide any useful information,” Roberts told Agência FAPESP from Bangkok, Thailand, where he currently lives.

The DEGy Negro River Expedition searched the area where Iracema caiana was collected, as recorded by Tyson Roberts in the late 1960s, but did not find the electric fish (photo: Thiago Loboda/MZ-USP)

Drought

“In general, we found a much smaller number of fish in this collection, in terms of species diversity and biomass. One hypothesis is that the great drought at the end of last year may have caused the fish that didn’t die to migrate to the headwaters of the rivers,” says Carlos David de Santana, a researcher associated with the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in the United States, a partner in the project.

“For example, two genera common in the aquatic environments we explored (Gymnorhamphichthys and Rhamphichthys) had not been caught [up to that point in the expedition], which could be an indication of the impact of the drought on the fish communities living in the region. Similarly, electrical signals were not detected with the appropriate equipment,” he adds (read more at: agencia.fapesp.br/51872).

Regarding Iracema caiana, Santana explains that another possibility is that the specimens collected in 1968 were brought to Roberts from another location, perhaps closer to the headwaters.

The Amazonian winter, the rainy season, lasts from September to February. However, in October 2023, the Negro River reached its lowest level in the 121 years that records have been kept. It was 12.70 meters in Manaus, while the previous record, set in 2010, was 13.63 meters.

Although it has rained again and the volume of the river has increased, the amount of rainfall is much lower than in previous years. In January, 110 millimeters of rain was considered “very dry” based on the average of the last two decades.

When the expedition visited the Negro basin in February, rainfall was even scarcer at 104 millimeters.

“The areas where the samples were taken are very well preserved and no signs of human alteration or impact were found. We now have to see if the species is actually present in another area or if it simply wasn’t found, which is quite common in this type of study,” explains Lucia Rapp Py-Daniel, a researcher at the National Institute for Amazonian Research (INPA), who also participated in the expedition.

From Itaquera, the team went to Barcelos (Amazonas state), where they obtained more fuel and food. The next destination was the Preto River, in the municipality of Santa Isabel do Rio Negro, also in Amazonas.

The DEGy Negro River Expedition team trawls for fish in a creek of the Jauaperi River (photo: André Julião/Agência FAPESP)

Watch all the episodes of the Field Diary – Rio Negro series at: agencia.fapesp.br/en/field-diary.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/51873