During the two weeks of the DEGy Negro River Expedition between Manaus and Santa Isabel do Rio Negro (Amazonas state), 27 species of sarapó were collected (photo: Phelipe Janning/Agência FAPESP)

Published on 06/06/2024

By André Julião, from Santa Isabel do Rio Negro | Agência FAPESP – In the Amazon, the same stretch of stream can have enough ecological differences to have fish that are quite distinct from each other, even if we only consider the electric fish, the sarapós and poraquês.

During the two weeks of the DEGy Negro River Expedition, between Manaus and Santa Isabel do Rio Negro, 27 species of sarapó were collected. It is estimated that the Negro River basin is home to about one hundred species of Gymnotiformes, as the electric fish group is called.

: Among the other fish collected, some sarapós stand out: the group constantly emits electrical signals and can be detected by a special device (photo: André Julião/Agência FAPESP)

Collecting and analyzing these fish allows us to better understand their diversity and evolution, as proposed by the project supported by FAPESP, under which the expedition took place this February, led by the Museum of Zoology of the University of São Paulo (MZ-USP). The reports of the trip make up the Field Diary – Negro River series, the episodes of which can be viewed at: agencia.fapesp.br/en/field-diary.

One day, the researchers were pointing the device used to detect electric fish at the sandy bottom of a stream when they heard the discharges, converted into sound, of Gymnorhamphichthys bogardusi. A few meters away, in an area full of dead leaves, another signal, this time from Hypopygus lepturus.

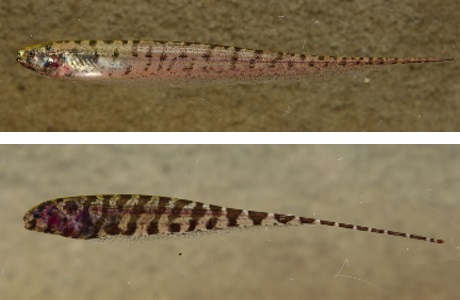

One is elongated and translucent, an adaptation to life under the sand. The other is full of brown spots that make it look very much like the rotting leaves that accumulate at the bottom of the igarapé.

Sarapós that hide in the sand, such as Gymnorhamphichthys bogardusi, are translucent and elongated, an adaptation to this type of environment photo: André Julião/Agência FAPESP)

“This is not unique to electric fish. Animals, in general, adapt to their habitat and can acquire similar characteristics even though they come from completely different groups, which is called evolutionary convergence,” explains Carlos David de Santana, a researcher associated with the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in the United States, a partner in the project.

In this case, there is more than one species of sarapó that is translucent and has an elongated body, such as Gymnorhamphichthys rondoni and Gymnorhamphichthys rosamariae, for example. There are also some that are mistaken for leaf litter (loose leaf cover on the ground).

Other differences can occur between populations of the same species, depending on where they occur. In the case of the sarapós, the same species can have a longer or shorter tail, depending on the watershed in which it lives.

In the Negro River, where the electrical conductivity of the water is low, the tail of the sarapós tends to be longer in order to better transmit the electrical signals that allow these fish to locate each other and, for example, find sexual partners.

Thus, the same species may have a smaller tail in waters with higher conductivity, such as those in the Amazon River basin.

“It’s like older radio antennas. If the signal wasn’t good, you’d turn the antenna up until you tuned into the station. In the same way, the longer tail makes it possible to better capture and transmit electrical signals when the environment is not so favorable for the propagation of these waves, as is the case in the Negro River basin,” points out Raimundo Nonato Gomes Mendes Júnior, an environmental analyst at the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio) and a doctoral student at MZ-USP.

A longer tail can also have its disadvantages, however. There are species, including of sarapós, that specialize in eating the tails of sarapós. The tail filament, as experts call it, regenerates, and the vital organs of the electric fish are closer to the head. That is why they can continue to feed and reproduce even if their bodies are missing a few centimeters.

Sarapó

Compared to poraquês, sarapós are much more diverse and abundant. Of the 250 or so species of the electric fish order (Gymnotiformes), only three are poraquês and all the others are sarapós, which are also known as ituí and tuvira. Some species are bred in captivity to serve as live bait.

For those who study electric fish, one advantage of this group over other fish is that they can be detected even without being seen. With the device that detects the electrical signals, it is possible not only to know that the animals are there but also to differentiate between genera and even some species.

Microsternarchus bilineatus collected by MZ-USP master’s student Vinicius Cardoso during the DEGy Negro River Expedition (photo: André Julião/Agência FAPESP)

“In general, electric fish use a low-voltage discharge for navigation and communication. In addition, some researchers have used the characteristic of the discharge of the electric organs as a taxonomic feature, meaning that in addition to the internal and external anatomy and DNA, the discharge of the electric organ also helps to identify species of Gymnotiformes,” says Santana.

On the boat, after the collection, the researcher explained this while a small sarapó of the species Brachyhypopomus bennetti swam in an aquarium on the table in front of him. In the water, two electrodes were connected to a recorder that recorded the animal’s discharge, which was converted into sound.

The noise produced by the discharge of this species has a pattern very similar to that of the weak discharge of the poraquê, a paused sound (“poe-poe-poe-poe”).

Above, Brachyhypopomus bennetti, a species of sarapó that emits electrical impulses in a pattern similar to that of the poraquês, perhaps to confuse the predator; below, Hypopygus lepturus, a sarapó with a color pattern that is confused with the leaf litter in which it is normally found (photos: Douglas Bastos)

“In the natural environment, the poraquê can prey on some species of sarapó. One theory is that this species produces a discharge similar to that of the poraquê to avoid being eaten by it,” explains the researcher.

The sarapó that “imitates” the poraquê is removed from the aquarium and another species is put in its place. Now, the electrodes connected to the recorder register a different, constant sound, more like that of a single-engine airplane (“poeOEoeOE”).

Another difference between the poraquês and the sarapós is that the former can interrupt its weak discharge for a few moments. Sarapós, on the other hand, spend their entire lives emitting electrical signals, which makes it difficult for them to escape detection by other electric fish that might eat them, but guarantees their navigation, search for prey and communication with mates. With small eyes, their vision is quite limited.

With each sarapó the team collects, the electrical discharge is recorded and saved as an audio file that can then be analyzed with special software. Santana and Mendes are creating a database of these discharges that can be used for comparative studies.

“Can discharges vary between different populations of the same species, for example? Does a sarapó from the Negro River have a different ‘accent’ from another in the Amazon River? These are the questions we’ll try to answer,” concludes Mendes.

View all the episodes of the Field Diary – Negro River series at: agencia.fapesp.br/en/field-diary.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/51876