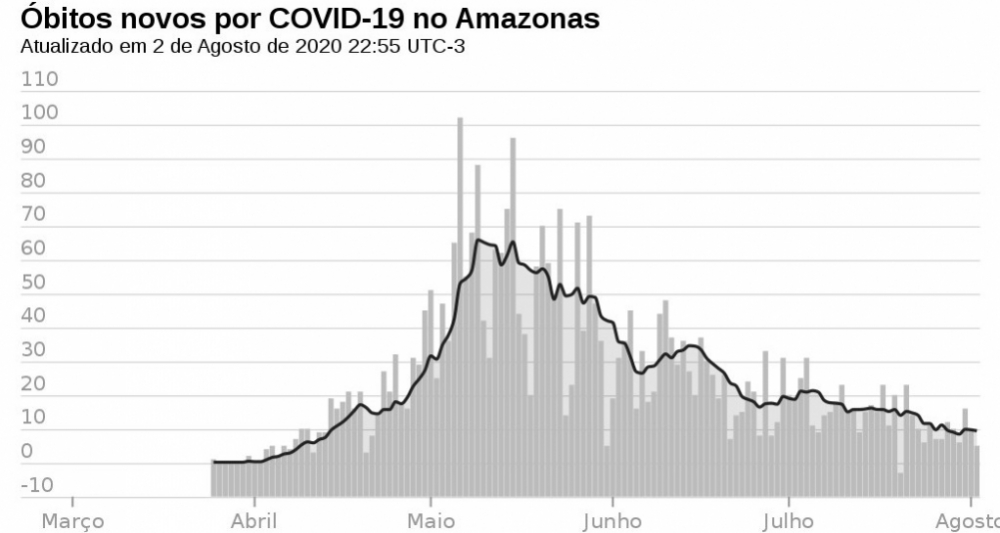

Specialists discussed the situation in a webinar held by Agência FAPESP and Canal Butantan. However, they stressed that achieving herd immunity should not be public policy, as clearly shown by the tragic death toll suffered in Manaus, the state capital of Amazonas (graph showing daily deaths from COVID-19 in Amazonas updated to August 2: Wikimedia Commons)

Published on 03/19/2021

By Karina Toledo | Agência FAPESP – The epidemiological pattern of COVID-19 in the state of Amazonas, Brazil, suggests what would happen in much of the world if governments let the pandemic follow its natural course and took only a few effective measures to minimize contagion. The already fragile healthcare system in Amazonas was overwhelmed by mid-April, only a month after confirmation of the first case in the state capital Manaus. By end-May, the city’s authorities were digging collective graves to bury the victims, but the number of daily new cases and deaths peaked and began trending down around this time. The downtrend has continued in the state, persisting even since June, when stores and schools were allowed to reopen, and despite the finding by several studies that less than 30% of the population has developed immunity against the novel coronavirus.

Experts who participated in a webinar held on August 4 by Agência FAPESP and Canal Butantan believe that the data for Amazonas corroborate a hypothesis that is starting to gain strength in the scientific community: the threshold for collective or “herd” immunity to SARS-CoV-2 may be reached when approximately 20% of the population has been infected, i.e., much sooner than estimated by modeling studies conducted early in the pandemic, according to which the threshold was between 50% and 70%.

The possibility of a relatively low herd immunity threshold had been previously raised by Portuguese biomathematician Gabriela Gomes, currently at the University of Strathclyde in Scotland (UK), and her group, which includes researchers at the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil. The group’s findings were based on projections produced by a mathematical model that takes into account variations in susceptibility and exposure to the virus among individuals in a given population (read more at: agencia.fapesp.br/33832).

“We came to the conclusion that this heterogeneity can change the results significantly and in a positive direction,” Gomes said during the online seminar. “It means the epidemiological curve should be shorter than projected by homogeneous models [which ignore variations in individual susceptibility and exposure], and the herd immunity threshold should be lower than estimated by the classical models.”

However, she stressed that the epidemic is not over simply because the herd immunity threshold is crossed. Transmission chains are already in progress, so the total number of cases will continue to rise, albeit more slowly, and could potentially reach a number corresponding to twice the number at the peak of the contagion curve.

“With careful mitigation, we can reduce the difference between the number of infections when herd immunity is reached and the final magnitude of the epidemic,” she said. “This requires control of the localized outbreaks that are occurring and measures such as contact tracing.”

Bernardo Horta, an epidemiologist at the Federal University of Pelotas (UFPEL) in Rio Grande do Sul, noted that the findings of the Epicovid seroprevalence survey, the largest study conducted in Brazil to measure the proportion of the population with antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, were in line with the projections produced by the “heterogeneous model” developed by Gomes.

In the first wave of tests performed as part of UFPEL’s survey on May 14-21, over 5% of the population was found to be infected in only a few cities in the North region and Fortaleza in the Northeast. In the third and last wave (June 21-24), the level of seroprevalence exceeded 5% in almost all of the North and Northeast, as well as in the city of Rio de Janeiro in the Southeast.

The current contagion rate (Rt) in these same places is less than 1, meaning that each infected person transmits the virus to less than one other person on average, and the number of new cases continues to trend down.

Even in towns such as Breves, Pará (in the North), where antibodies against coronavirus were detected in 24.8% of the people tested in the first wave of the survey, the level of seroprevalence has not surpassed 30% at any time. In some parts of the North region, Horta said, the proportion with antibodies fell between the first and third wave of testing. The exact reason for the decline is not yet understood.

For Júlio Croda, an infectious disease specialist at the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), only herd immunity can explain why the contagion rate is below 1 in the North, Northeast and Rio, even without proper social distancing. Nevertheless, he stressed that targeting herd immunity cannot be a matter of public policy since no health service can provide the number of intensive care beds needed to cope with the first wave of the disease without mitigation measures.

“Manaus had the highest level of excess deaths among all Brazilian cities, reaching 500%,” Croda said. “The number of registered deaths [in 2020] was five times that of previous years, and 90% were due to respiratory problems. The case of Amazonas enables us to understand what the natural history of the disease looks like, but we’re not proposing this as a strategy. It’s the portrait of a tragedy. We must learn from the actual data.”

Future scenarios

Assuming that the projections produced by Gomes’s “heterogeneous model” turn out to be roughly accurate, Croda estimates that the city of São Paulo, Brazil’s first COVID-19 epicenter, is close to the herd immunity threshold. In the interior of the state of São Paulo, however, the contagion curve is still rising.

“Studies show seroprevalence in the city of São Paulo at around 11%, reaching 16% in some poor neighborhoods,” he said. “In Manaus, it reached 14.8% at the peak of the epidemic. São Paulo has done its homework well, especially in the metropolitan area, where excess deaths reached 28%, in contrast with 500% in Manaus.”

For Marcos Amaku, an epidemiologist at USP, even if the herd immunity threshold is 20%, this corresponds to 8 million people in the state of São Paulo. The number of confirmed cases is currently above 700,000, and assuming the actual number is seven or eight times higher, the threshold is still a long way off.

“Most towns and cities in the state haven’t reached 10% in terms of seroprevalence. At the current rate, we won’t reach 20% for some time,” said Dimas Tadeu Covas, head of Butantan Institute and a discussant during the webinar.

For Croda, however, the epidemiological data suggest that different levels of seroprevalence may act as a herd immunity threshold in different places as long as mitigation measures, such as the mandatory use of face coverings and social distancing, are in effect.

“I’m optimistic,” he said at the webinar. “I believe the worst is over, except in the South and part of the Center-West. I say that on the basis of the heterogeneous model and acknowledging the tragedy of almost 100,000 registered deaths [COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil surpassed 100,000 deaths in August 8th, and the 7-day rolling average of deaths has been over 900 ever since]. There’s nothing normal about almost 1,000 deaths per day for 60 days. But the worst is nearly over in São Paulo, a state with 44 million inhabitants, and that’s very significant for Brazil. Once we’re past the plateau in the death curve – we don’t know how long that will take because it reflects the rise in other regions [the South and Center-West] – I expect the curve to trend down.”

A complete recording of the webinar is available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=SkKSjISTQRk.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/33945