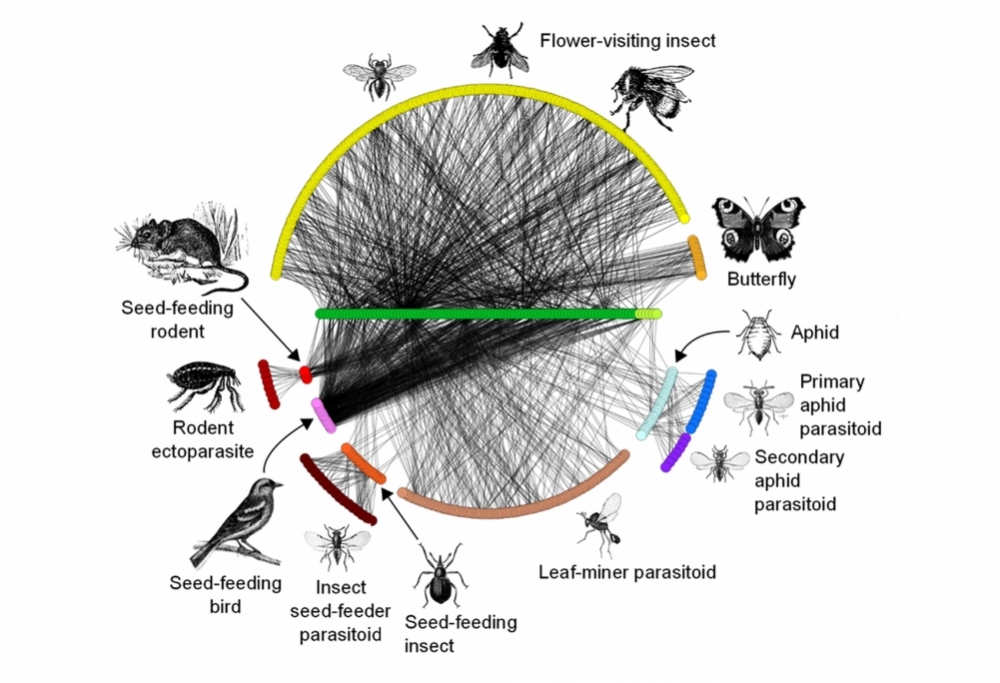

Technique known as DNA metabarcoding helps scientists identify species in an area and understand how they interact (image: Pocock, Evans & Memmott / Science [2012]; Ecology Letters [2013])

Published on 05/13/2021

By André Julião | Agência FAPESP – By placing a small sample of river water into a device smaller than a smartphone, scientists can determine what species of fishes, fungi, algae, invertebrates and bacteria live in the river. This method is possible due to portable DNA sequencing, a technology that is used to investigate not only species but also interactions among them.

According to Darren Evans, Reader in Ecology and Conservation at Newcastle University in the United Kingdom, the device and the knowledge it helps produce can be used to enhance ecosystem management and restore degraded areas.

Evans spoke about the subject at FAPESP Week London, a symposium held in the capital of the UK on February 11-12, 2019.

“What’s been done so far is to collect specimens and use sequencing to obtain unique DNA barcodes for the species in question,” he said. Evans was the principal investigator for a study conducted in collaboration with two Brazilian researchers supported by FAPESP (read more at: agencia.fapesp.br/29663).

Instead of whole genes, DNA barcoding entails sequencing only a key portion that yields sufficient information to identify a species.

“All this information goes into public repositories and anyone can access it, but it still takes a long time and is very costly. What we did is called metabarcoding, which uses a different platform that can process perhaps 1,000 individuals in a single sequencing round. Moreover, we didn’t just use the results to create DNA barcodes for each specimen. We also analyzed all the associated organisms, such as parasites, fungi and so on,” Evans said.

The new method extends DNA-based species identification to a community comprised of individuals belonging to many groups of species playng distinct roles in an ecosystem. Data on interactions among these individuals can be used to map the networks to which they belong and describe the biodiversity in an area very quickly.

“This will revolutionize the way environmental monitoring is done. You can go to a place and find out on the spot about all the organisms that live there and how they interact,” Evans told Agência FAPESP.

This highly detailed information can be used to refine ecosystem management and even restore ecosystems where necessary by means of biodiversity engineering.

In many habitats, important species become extinct, making way for others that perform the same functions as the species that have disappeared. Evans and collaborators believe this scenario can be modeled to determine which species should be in the network.

“The outcome is a list of the species that could enhance the resilience of the network,” he said. “The challenge is putting these theoretical ideas into practice to restore natural or agricultural systems.”

Nitrogen

The restoration of degraded agricultural systems was the focus of another presentation delivered during the same session of FAPESP Week London. A study conducted by British and Brazilian researchers involved working with farmers to help them learn new nitrogen use techniques to efficiently manage and thereby enhance crop yields.

“The farmers don’t always like the techniques we offer because they’re hard to apply or for other reasons. This is an issue we have to take into account,” said Sacha Mooney, Professor of Soil Physics at the University of Nottingham (UK), during his presentation.

Mooney outlined a project called the NUCLEUS Virtual Center, which uses the latest technologies to recommend new efficient nitrogen use management strategies to farmers in the UK and Brazil. The project is supported by FAPESP and UK research councils. The principal investigator in Brazil is Ciro Rosolem, a professor at São Paulo State University’s Botucatu School of Agronomy (FCA-UNESP).

“In the first stage, we show farmers a few examples of successful soil nitrogen restoration and yield improvement. The next stage involves working with those who don’t use the practices in question because they’ve encountered difficulties. We tackle the problem with them and work in partnership,” Mooney said.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/30032