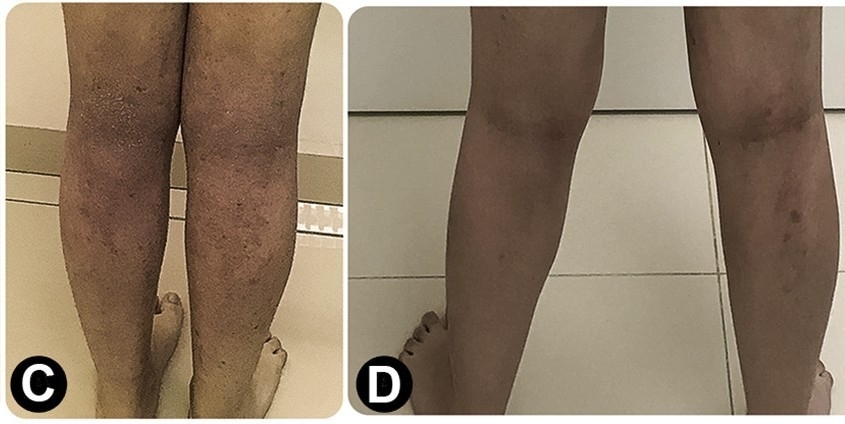

A fifteen-year-old female patient with atopic dermatitis lesions on her legs (C) and pictured after a period of 18 months of treatment (D) after which she displayed marked improvement (photos: Sarah Sella Langer et al./Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: in Practice)

Published on 01/31/2022

By Luciana Constantino | Agência FAPESP – Treatment with house dust mite extract was found to be effective against signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis (eczema), a chronic inflammatory disease that results in itchy, swollen and cracked skin. Researchers at the University of São Paulo’s Ribeirão Preto Medical School (FMRP-USP) in Brazil studied the effects of sublingual immunotherapy with extract of Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, a ubiquitous dust mite, administered to patients in drops for 18 months.

Dust mites are microscopic arachnids that live in house dust and feed on dead human skin cells.

After 18 months of treatment, pruritus (itchy skin) and lesions diminished, almost disappearing in some cases. Side-effects were rare, mainly consisting of mild local reactions that did not last long.

The study was supported by FAPESP and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). An article reporting the findings is published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: in Practice.

Allergen immunotherapy consists of administering vaccines produced with the substance (allergen) to which the patient is allergic. Patients repeatedly receive doses with gradually increasing allergen concentration, with the aim of reducing sensitivity and inducing tolerance of dust mites, pollen or insect venom, among others.

The study involved a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, considered the gold standard for assessment of drug efficacy. The trial was conducted between May 2018 and June 2020 at the Clinical Research Unit of FMRP-USP’s hospital. A group of 66 patients received placebo or dust mite extract three days per week for 18 months. They were attended by medical doctor Sarah Sella Langer, a graduate scholar at FMRP-USP and first author of the article.

“Previous research had already shown that dust mite immunotherapy worked well in cases of rhinitis, conjunctivitis and allergic asthma, but for atopic dermatitis the results were uneven, especially when it involved subcutaneous injections. When sublingual immunotherapy came along, with less probability of adverse side-effects such as systemic reactions, we decided to investigate and obtained positive results,” said Luisa Karla de Paula Arruda, Professor of Clinical Medicine at FMRP-USP and last author of the article.

The fact that the extract is given in the form of drops is an advantage, she explained, because it facilitates the administration of increasing doses and avoids the use of fixed dose throughout the treatment, as in the case of sublingual pills, for example.

In the study, the first three months entailed an initial dilution of 1:1 million volume:volume (v:v), progressing to 1:100,000 v:v, 1:10,000 v:v until it reached 1:10 v:v, administered for a period of 15 days. The placebo solution was identical to the diluent of the extract, comprising water and glycerol, and administered according to the same schedule.

The sublingual immunotherapy substance was supplied by a Brazilian laboratory licensed to prepare and commercialize it from a lyophilized extract of D. pteronyssinus produced in Spain as the result of processing a culture of these mites, which are macerated, diluted and centrifuged to obtain the extract.

“Dust mites should be environmentally controlled by using waterproof mattress covers and pillow cases and removing cushions, carpets and rugs. Topical treatment is also recommended for the eczema-like skin allergy, with hydration and use of specific medications, but it’s often insufficient for adequate control of symptoms,” Arruda said. “Immunotherapy is a step further and can lead to a clinical improvement that was absent before, even if other measures are also taken. Our study points to a practical application, which allergists can offer their patients.”

Atopic dermatitis causes inflammation of the skin, itching, rashes, and bumps that may leak fluid and crust over. It mainly affects knee and elbow bends, and may be associated with asthma and rhinitis.

Environmental factors may contribute to development of the disease in genetically predisposed people, such as allergy to dust mites, pollen, mold, pets, and exposure to cleaning products or other chemicals. Dry air, intense cold, heat, sweat and stress can intensify the symptoms, as can infection of cracked skin by bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, and by viruses and fungi.

Little is known for sure about the prevalence of atopic dermatitis, and estimates range from 0.2% to 20%. However, some 30% of the population have allergies of some kind, among which rhinitis and asthma are particularly common, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Results

The researchers deployed several tools to analyze responses to the treatment. One was SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis), an internationally accepted clinical tool used to assess the extent and severity of the disease. It results in a score based on the percentage of the body affected and symptoms such as itchiness, swelling, dryness, etc., as well as insomnia. Less than 25 is considered mild, 25-49 moderate and 50 or more severe.

After 18 months, the score had fallen by 15 or more in 74.2% of the patients given immunotherapy, and by 55% from the initial baseline scores, compared with 34.5% for the control group given placebo. This difference was considered statistically significant, confirming the efficacy of the treatment. The results were similar using O-SCORAD (Objective SCORAD, leaving out patients’ assessments of symptoms).

The researchers also used a tool known as the Investigator Global Assessment (IGA), a five-point scale ranging from 0 to 4, where 0 indicates clear skin, 1 almost clear, 2 mild eczema, 3 moderate, and 4 severe. The number of patients graded 0-1 was far higher in the immunotherapy group (14 out of 35, compared with 5 out of 31 in the control group).

The two groups were not significantly different according to the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).

“The design of the study was innovative,” Arruda said. “Another novelty was the use of data for Brazilian patients. Most research on this topic uses data from other countries, but in the case of allergies, the results may vary widely. I think it’s important to do research with our own patients so that we can develop additional, more targeted treatments.”

The article “Efficacy of house dust mite sublingual immunotherapy in patients with atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial” is at: www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2213219821012502?via%3Dihub.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/37831