Galetti, CBioClima’s Dissemination Coordinator, in the Mata de Santa Genebra (photo: Daniel Antônio/Agência FAPESP)

Published on 08/28/2024

By André Julião, from Mata de Santa Genebra (Campinas) | Agência FAPESP* – Mauro Galetti has been with the giant tortoises of the Galapagos, the orangutans of Borneo, the iguanas of the Bahamas, the araçaris of the Serra do Mar, but he really gets excited when he sees howler monkeys in a little patch of Atlantic Forest in the city of Campinas (state of São Paulo, Brazil), the Mata de Santa Genebra.

In this 252-hectare fragment, about seven kilometers from the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP), the Dissemination Coordinator of the Center for Research on Biodiversity Dynamics and Climate Change (CBioClima) – a FAPESP Research, Innovation, and Dissemination Center (RIDC) located at the São Paulo State University’s Institute of Biosciences (IB-UNESP) in Rio Claro – began his scientific journey (read more at: agencia.fapesp.br/51782/).

It is no coincidence that the Mata de Santa Genebra is the starting point for Um naturalista no antropoceno – um biólogo em busca do selvagem (“A naturalist in the Anthropocene – a biologist in search of the wild”, Editora Unesp, 2023), a book written by the UNESP professor in which he recounts his career based on the different places he’s been as a scientist.

“The beginning of my degree course was very theoretical and I was very frustrated with being in the classroom. How can you learn biology within four walls? This is where that changed for me. Looking for howler monkeys and fruit, I began to understand how life is structured,” the researcher tells Agência FAPESP, under the shade of a jatobá (Hymenaea courbaril) at the entrance to a forest trail.

It was based on the observations and notes he made here that he published his first scientific article at the age of 19, during his undergraduate studies at UNICAMP’s Institute of Biology. With so much time spent walking the trails, collecting seeds, observing animals, and tabulating the information, he created a database that is still used today by researchers all over the world.

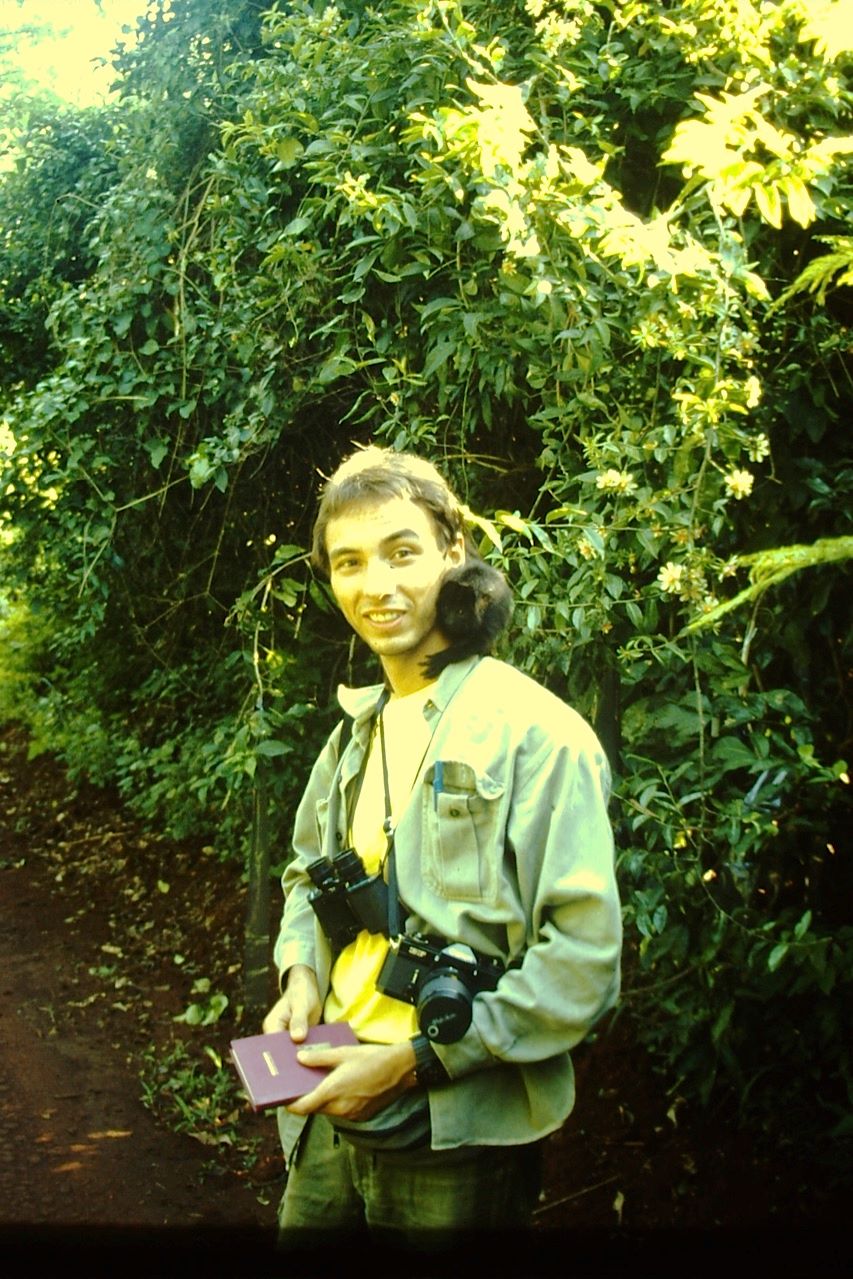

Galetti at the age of 19, in the Mata de Santa Genebra, with a howler monkey cub on his shoulder. The dispersal of seeds by these primates was the subject of the author’s first scientific article (photo: personal archive)

“The Mata de Santa Genebra is probably one of the most studied Atlantic Forest remnants in the world. Hundreds of master’s dissertations and doctoral theses have been written using data collected here,” he says.

The fluidity of the book’s language recalls that of other scientist-writers, notably the Americans Edward O. Wilson and Jared Diamond, Galetti’s avowed inspirations.

“I grew up in biology reading the work of these authors, and I felt there was a lack of more books like this in Brazil. Mine is just one story. With this book, I hope to create not only readers but also other authors,” he says.

“The Anthropocene is real”

In March of this year, shortly after the book’s publication, the concept of the Anthropocene (from the Greek anthropos, meaning human, and kainos, meaning new) as a new geological epoch to succeed the Holocene was rejected by the International Commission on Stratigraphy of the International Union of Geological Sciences.

However, even geologists, and especially scientists from other fields, agree that human activity since the Industrial Revolution has caused changes on Earth that will be evident even in the distant future. As someone who studies species losses and the interactions between them, Galetti could not think otherwise.

“The Anthropocene exists, it’s real, just look at what’s happening on the planet. The vast majority of scientists understand that our influence, especially climate change and changes in biodiversity, is transforming the Earth. We’re causing the extinction of several species, entering a sixth mass extinction. This is irreversible. We’re changing the climate. Several species have changed their evolution because of human beings,” he states.

In the first chapter of the book, the author lists and exemplifies the main characteristics of a geological epoch that is now being created by human activity: the appearance of new chemical elements and molecules (such as those contained in pesticides), new rocks (concrete and plastic rocks), new fossils (chewing gum and PET bottles), the emergence (domestic animals and plants) and extinction (passenger pigeon, dodo, giant sloth) of species, as well as changes in the climate (which, among other problems, cause more extreme events, such as the recent rains in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul).

Galetti and a Galapagos tortoise, on one of the islands of the legendary archipelago visited by Charles Darwin (photo: personal archive)

Mars is not an option

But more than reflections on the planet’s past and future, A Naturalist in the Anthropocene is a personal and scientific journey through forests, savannahs, and tropical islands.

In it, the reader can discover a paradise in the state of São Paulo, called Saibadela, in the Ribeira River Valley region, an isolated and humid place where countless species of birds feed on hundreds of different fruits, where animals and plants reproduce in a harmonious cycle that is difficult to find in the Atlantic Forest, which has only 12% of its original cover.

On the way between the chapters, you can also visit Borneo, one of the Indonesian islands where the legendary orangutans live, but also the kalaus, bearded boars, and sun bears, from which Galetti once had to flee during his post-doctoral studies.

“Borneo and the Galapagos Islands, both visited by Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Darwin, were very important in my training as a naturalist,” says Galetti.

Galetti with Galapagos iguanas, endemic to the archipelago (photo: personal archive)

In addition to these islands, the archipelagos of the Bahamas and Fernando de Noronha are other parts of the world visited by the author. With his students and partners, Galetti studied how invading rats and mice are altering seed dispersal previously carried out by native birds and reptiles.

The conclusions of this scientific journey, which could be pessimistic, actually bring some hope. This is good news because Galetti is part of the team that is trying to make a difference by studying the effects of and possible solutions to man-made problems at the recently created CBioClima.

“The Center for Research on Biodiversity Dynamics and Climate Change brings together researchers and students who, working on these topics, have realized that it’s necessary to join forces in a single center with resources, in this case from FAPESP, to advance on questions that we cannot answer individually. Together, we can take a leap forward in scientific knowledge and seek environmental solutions for Brazil,” he says.

For the naturalist, at the same time as creating the problems of the Anthropocene, man has the opportunity to solve them. “Some will take longer, others less [to solve], but I take an optimistic view. I think that never in the history of mankind have so many people been concerned about the environment. It’s what Professor Edward O. Wilson calls biophilia. We need other animals, other plants, other organisms. You can’t live alone, so migrating to Mars isn’t a solution.”

* Daniel Antônio collaborated.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/52628