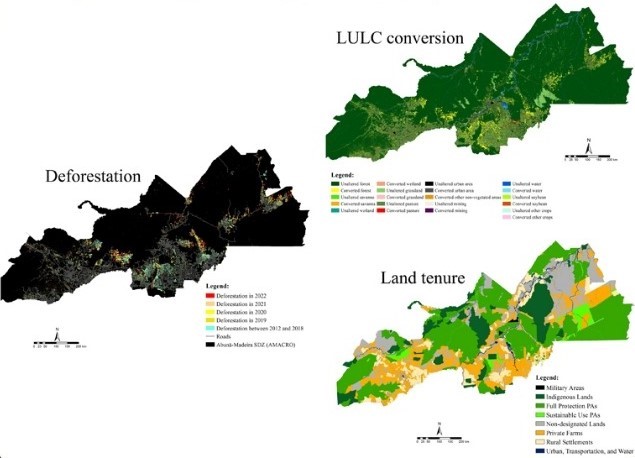

The study used official remote sensing data to analyze an area of some 454,000 square km that contains 32 municipalities and is considered the new “deforestation arc” (image: Michel Chaves)

Published on 05/06/2024

By Luciana Constantino | Agência FAPESP – The Brazilian government is discussing the creation of an “agricultural development zone” at the confluence of three states in the Amazon region – Amazonas, Acre and Rondônia (hence the proposed acronym AMACRO). Meanwhile, deforestation in the region continues, with the planned zone accounting for 76.5% of deforestation in the three states between 2018 and 2022, warns an article published in the journal Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation.

According to the authors, deforestation has accelerated in the region, alongside land speculation and conversion of forest into pasture and cropland, since the government announced the plan to create the agricultural zone, now called the “Abunã-Madeira Sustainable Development Zone” (SDZ). They used official data based on remote sensing to analyze an area in southern Amazonas, eastern Acre and northwestern Rondônia measuring some 454,000 square kilometers (km²), about the size of Sweden, the fifth-largest European country. Sometimes referred to as the new deforestation arc, the area contains 32 municipalities and has 1.7 million inhabitants. Planning and organization of the SDZ is in progress.

“My postdoctoral research at INPE [Brazil’s National Space Research Institute] involved an analysis of the expansion of the agricultural frontier in the Cerrado, but I found that it was also advancing in the Amazon, especially in the area in question. We therefore set out to understand what was happening there and arrived at this situation of land speculation and intense pressure,” Michel Eustáquio Dantas Chaves, first author of the article, told Agência FAPESP. Chaves is a professor at São Paulo State University (UNESP) in Tupã.

He led an earlier study that demonstrated the efficacy of using SENTINEL-2 satellite images to detect the advance of the agricultural frontier as one of the drivers of abrupt land use changes.

Deforestation rates in Legal Amazonia, an area of more than 5 million km² comprising nine Brazilian states (Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Maranhão, Mato Grosso, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima, and Tocantins) created by federal law to promote environmental protection and regional development, rose gradually in the last decade, surpassing 10,000 km² per year and reaching 13,038 km² in 2021, the highest level since 2006, according to PRODES, INPE’s Amazon Forest Satellite Monitoring Service. However, after four consecutive years of high rates, annual deforestation fell 22% to 9,001 km² between August 2022 and July 2023.

In an analysis of deforestation rates by land tenure, the researchers show that they were highest and rising on private property, but accelerated alarmingly in conservation units between 2018 and 2022.

Public land, a large proportion of the proposed SDZ, including extractive reserves and Indigenous territories, was also under growing pressure. In 2021, for example, 64% of deforestation occurred on public land.

The area contains 86 conservation units, 49 Indigenous territories and 94,199 km² of undesignated public forests (state-owned areas not assigned to a specific use, such conservation or settlement).

For the authors, the lack of environmental impact studies and socioenvironmental policies to protect traditional communities is a cause for concern, raising doubts about the viability and sustainability of the project.

“We know it’s important to implement a development zone, especially to assure access to paid work, production and economic growth for people who live outside major cities, but good governance is equally important to enforce the laws and to assure income generation and development rather than exploitation,” said Marcos Adami, corresponding author of the article and a researcher in INPE’s Earth Observation and Geoinformatics Division.

The other co-authors include Ieda Sanches (INPE), Katyanne Conceição (Pará State Department of Environment and Sustainability) and Guilherme Mataveli (INPE/University of East Anglia).

FAPESP supported the study via four projects (21/07382-2, 19/25701-8, 20/15230-5 and 23/03206-0).

The idea of establishing the SDZ originally focused on soybean growing, Chaves recalled, and for this reason it was at one time referred to as a ”northern MaToPiBA”. Almost 12% of the nation’s soybean crop is grown in the area known as MaToPiBa, a portmanteau of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia, parts of which form another agricultural frontier and are seeing an increase in conversion of native vegetation into pasture and cropland.

The section of the Brazilian government’s portal devoted to SUDAM, the Superintendency for Development of the Amazon, states that the Abunã-Madeira SDZ will foster social and economic development by promoting the bioeconomy, sustainable agriculture (fruit growing, fish farming and agribusiness), and multisector activities such as infrastructure, logistics, tourism, training and research. It also states that the SDZ may serve as a pilot project for similar ventures in other parts of the Amazon.

When Agência FAPESP asked the Ministry for Integration and Regional Development to comment on the plan, it pointed us to SUDAM, which has not replied to our request.

Main findings

Deforestation in the area surged in 2018 and thereafter, but had already begun to accelerate in 2012, according to the study. The uptrend coincided with a period of economic crisis and weakening environmental regulation in Brazil. Between 2012 and 2020, 5.2% of the area’s forest was converted to anthropic land uses, especially pasture (78%).

In absolute terms, deforestation increased in all land tenure classes, but the acceleration was most intense in conservation units, especially since the SDZ project was announced in 2018. In land reform settlements (assentamentos rurais), the highest level was 625.56 km² in 2021, 83.34% above the 2012-20 average (341.20 km²).

The study used data from PRODES, which has consistently maintained its methodology since 1988 and is considered the most accurate source for estimates of annual deforestation rates in the Amazon. This was combined with geographic information and data from the Rural Environmental Register (CAR) and the Land Management System (SIGEF).

All landowners are required to register with the CAR, which is supposed to ensure compliance with the Forest Code. The process is essentially self-declaratory. Landowners are also required to register properties with the Land Management System (SIGEF) administered by the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA) in order to obtain title, financing and permits for developments such as hydroelectricity or mining projects.

For penultimate author Felipe Gomes Petrone, a master’s candidate and remote sensing researcher at INPE, “Merely defining rural development zones without socioenvironmental impact assessments and public policies can do more harm than good to the agri-environmental sector.”

According to Adami, “farmers need to be strong allies of environmental protection because it raises yields and leads to many other improvements via conservation of natural factors such as rain, nutrient cycling, pollination and so on. Disruption of climate regulation and the useful water cycle for agricultural production in important producer states can lead to losses worth billions.”

The authors advocate diversified agricultural production in the SDZ, with appropriate environmental safeguards, strategies to add value to local production, and valorization of the standing forest.

The article “AMACRO: the newer Amazonia deforestation hotspot and a potential setback for Brazilian agriculture” is at: www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2530064424000099.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/51579