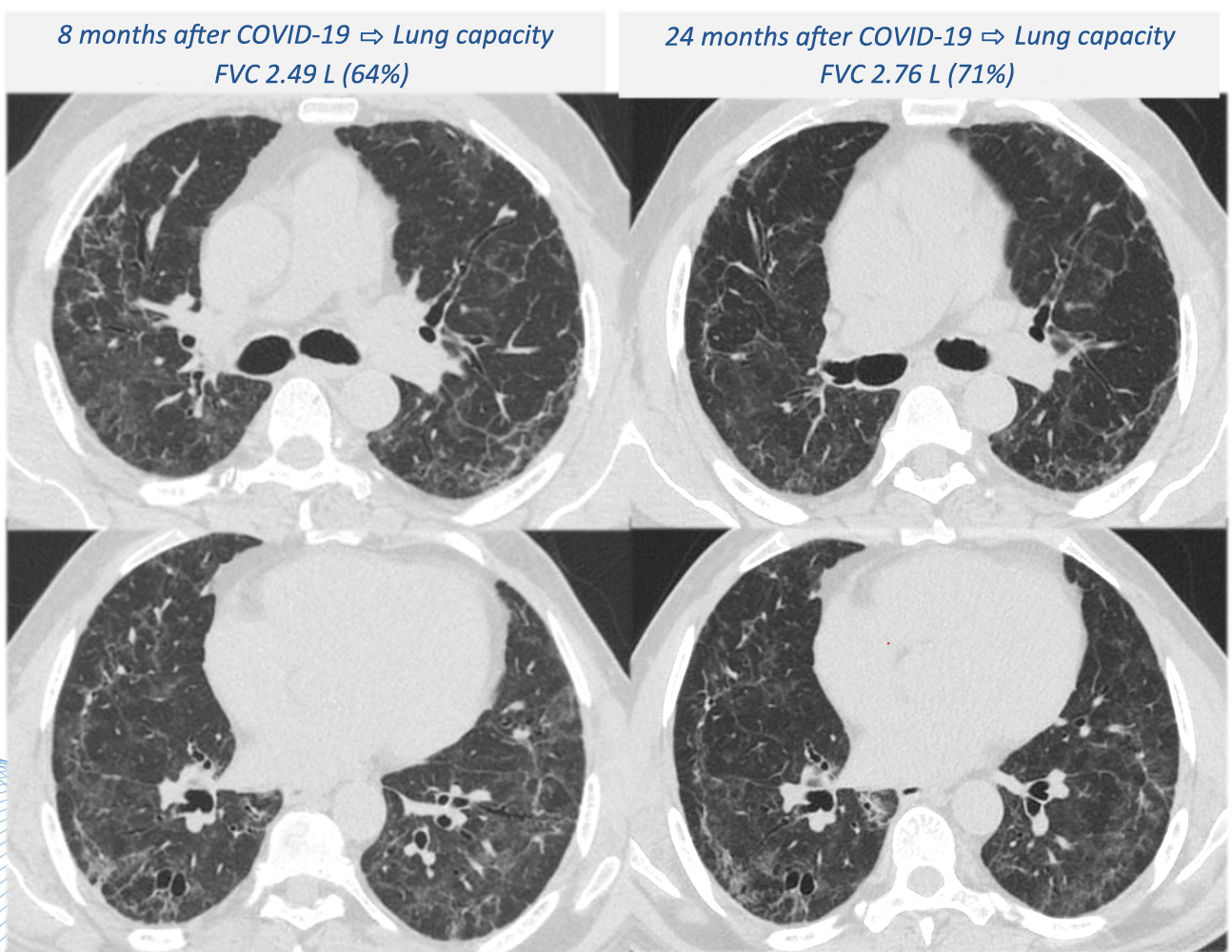

A small number (2%) of participants with fibrotic-like lesions displayed an improvement in their lungs compared with the assessment performed one year after discharge, but many more (25%) had worsened (image: HC-FM-USP)

Published on 07/08/2024

By Maria Fernanda Ziegler | Agência FAPESP – A study conducted in Brazil points to long-term functional abnormalities in their lungs two years after hospital discharge in most severe COVID-19 patients who had required intubation, and a return of pulmonary lesions after 24 months in some people who appeared to have fully recovered on being discharged. The study involved 237 patients admitted to Hospital das Clínicas, a hospital complex run by the University of São Paulo’s Medical School (FM-USP), between March and August 2020, and followed up between six and 12 months after discharge. The subset with pulmonary lesions was assessed after 18-24 months.

The vast majority (92%) were diagnosed with alterations in their lungs in both follow-ups: 58% exhibited inflammation and 33% had fibrosis (scarred tissue that becomes stiff and cannot properly perform gas exchange). A small number (2%) of those with fibrotic-like lesions displayed an improvement in their lungs in the second assessment, but many more (25%) had worsened.

An article reporting the findings of the study is published in The Lancet Regional Health – Americas.

The study was part of a project supported by FAPESP and Instituto Todos pela Saúde, an initiative led by Itaú Unibanco, Brazil’s largest private sector bank. The researchers are monitoring more than 700 patients for at least four years after hospitalization for treatment of COVID-19, with the aim of investigating the effects of SARS-CoV-2 in many areas, from genetics to physical, psychological and cognitive functions, in what has proved to be one of the world’s largest cohort surveys in the field.

“As far as pulmonary problems are concerned, older patients who required intensive care and mechanical ventilation showed signs of lung complications two years after being discharged from hospital. Further follow-up assessments will be needed to find out whether they’re permanent. Another interesting finding, which exemplifies the extent to which the virus has surprised all of us, was that the lungs of 20 patients had improved after a year but deteriorated after two years,” says Carlos Roberto Ribeiro de Carvalho, full professor at FM-USP and corresponding author of the article.

The fibrosis is a matter of keen concern – so much so that in the three-year post-COVID assessment (already completed but still being analyzed), the researchers included a lung biopsy via bronchoscopy to glean more detailed information on the alterations to lung capacity observed in previous CT (computerized tomography) scans.

“We need to find out whether what we’re seeing is scar tissue or early-stage fibrosis. The biopsy is important because it will enable us to decide whether to intervene with medication [corticosteroids or antifibrotics] to try to halt progression of the fibrosis,” Carvalho explains.

Scarring and fibrosis in the lungs can be caused by more than 200 factors, he adds. They include inhalation of coal, silica or asbestos dust by miners, factory operatives, construction workers and so on. Some inflammatory autoimmune diseases, such as scleroderma, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, can also cause scarring of pulmonary tissue and a decrease in respiratory capacity.

“This has been observed in other viral pneumonias, but the frequency seems to be higher in the case of SARS-CoV-2. It’s a problem that needs to be monitored since there are only two treatments for advanced fibrosis, and both are complex and expensive, involving costly medications or lung transplantation. So this is a very serious complication for the patient and a heavy burden for the healthcare system, especially the SUS [Sistema Único de Saúde , Brazil’s public health network],” Carvalho says.

Non-fibrotic but bronchiolitic

The study also identified another post-COVID pulmonary sequelae profile: patients who had not required intensive care but had been placed on oxygen supplementation were developing bronchiolitis and other types of small airway disease.

“Unlike patients who had been intubated and later found to have fibrosis, those who only received oxygen supplementation during their hospital stay were developing a form of bronchial disease, which we’re now studying,” Carvalho says.

The findings can help clinicians draw up new protocols for treatment of patients with post-COVID pulmonary sequelae or long COVID, he adds, noting that the main symptoms are fatigue and weakness.

“We observed that these two symptoms may be associated with three different factors. In some cases, fatigue and weakness can be due to lung disease, and in others to heart disease. A third possibility is a problem with muscles such as sarcopenia [loss of muscle mass, force and function],” he says.

“All this should be taken into account. Treatment will be different in each of these cases. Above all, it’s important to know that treatment exists. Our research project aims to increase knowledge of the sequelae of COVID-19 and how to treat them. This is what we’re after.”

The article “Post-COVID-19 respiratory sequelae two years after hospitalization: an ambidirectional study” is at: www.thelancet.com/journals/lanam/article/PIIS2667-193X(24)00060-7/fulltext.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/52158