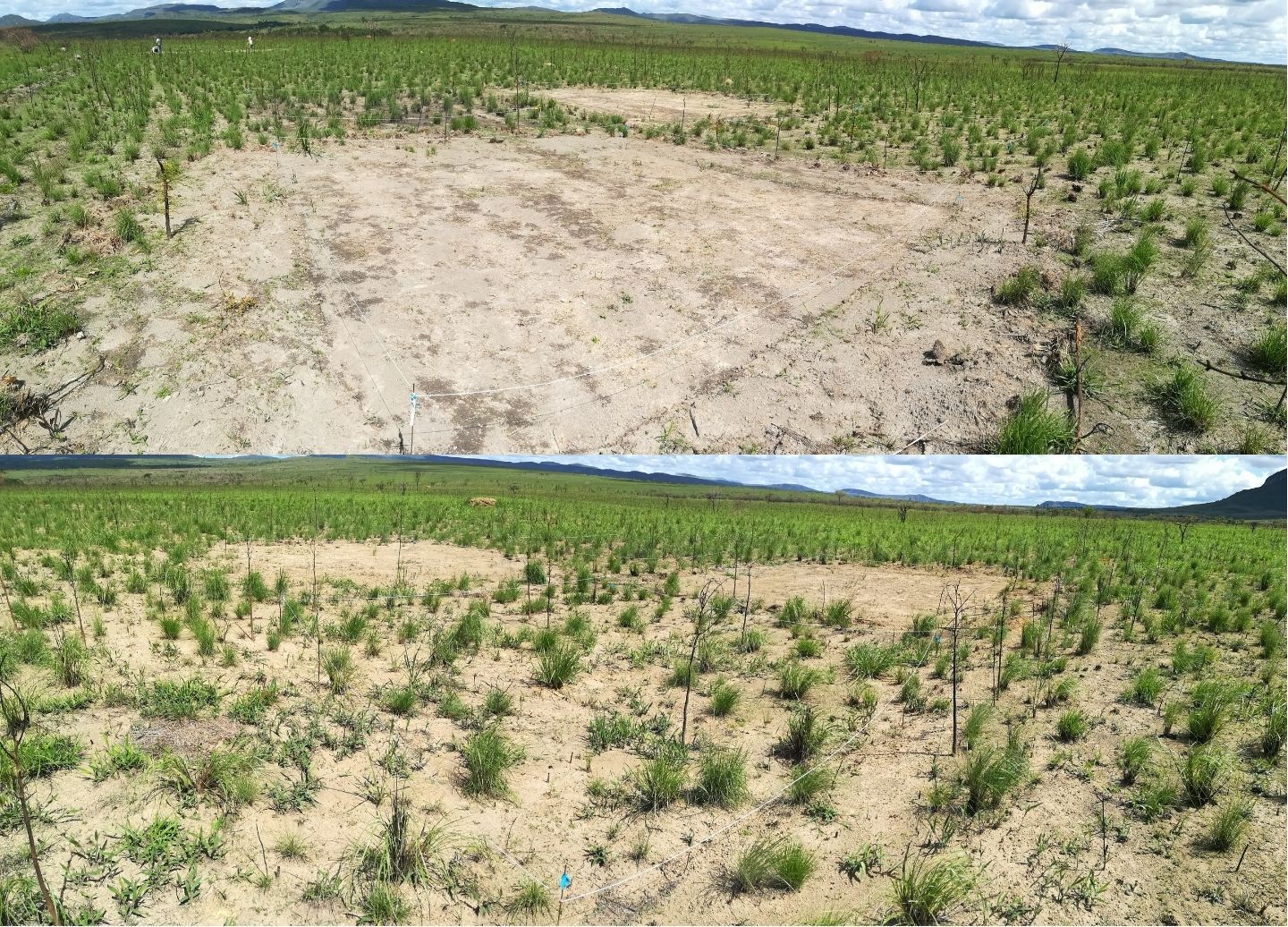

Application of iron sulfate in a restoration area in Chapada dos Veadeiros (photo: Demétrius Lira Martins)

Published on 03/17/2025

By André Julião | Agência FAPESP – In a study published in the journal Restoration Ecology, a group led by researchers from the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP), in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, points to a promising path for the restoration of the Cerrado, the Brazilian savannah-like biome.

Through an experiment conducted in the Chapada dos Veadeiros National Park in the state of Goiás, Central-Western Brazil, the authors demonstrated that, unlike some conventional restoration initiatives, no nutrients should be added to the soil when it comes to the Cerrado.

In a restoration area of the park, the researchers analyzed the growth of invasive grasses and native species after applying iron sulfate, which makes the soil more acidic and reduces nutrient availability. Where the mineral was applied, invasive plants were reduced by nearly 71%, without harming native plants.

“Cerrado plants have low nutrient requirements and grow slowly. The invasive grasses, on the other hand, grow quickly and require a lot of nutrients. The iron sulfate restores the soil to a state closer to the original, favoring the native plants and hindering the growth of the invaders,” explains Demétrius Lira Martins, who carried out the work during his postdoctoral studies at the Institute of Biology (IB) of UNICAMP, with the support of FAPESP.

The 50-hectare area was restored in 2016 after 30 years as pasture. Four years after the exotic grass was removed, the soil was prepared and native species were sown, the African grasses took over again.

In 2021, the restoration was resumed. This time, the experiment was designed to test the effect of soil acidification on the containment of the exotic grass. The researchers marked out 14 plots of 100 square meters (m²). Within each plot, they separated four smaller plots of 1 m² each, 10 meters apart.

In half of these plots, iron sulfate was applied to the soil prior to sowing native grasses and shrubs. Four months after the last application, samples of the plants growing in each plot, both native and exotic, were collected and weighed.

When the plots were compared, there was a 70.7% reduction in the biomass of the invasive species where acidification was applied, without harming the native species.

“Acidification increased the levels of aluminum in the soil, which is toxic to conventional plants. But native species cope very well. It’s no wonder that the first thing you do after clearing a Cerrado area for crops or pasture is liming [applying lime], which reduces the availability of aluminum and increases the availability of other nutrients,” says Martins.

At the top, an experimental plot where the soil was acidified at the beginning of the implementation has been cleared of invasive grasses and native species are slowly returning. In the other photo, the area that didn’t receive the iron sulfate has been taken over by African species (photos: Demétrius Lira Martins)

Strategies

The study is part of the project “Restoring dry Neotropical ecosystems: is the functional composition of plants the key to success?”, supported by FAPESP and coordinated by Rafael Silva Oliveira, professor at IB-UNICAMP.

The strategy presented now joins others developed by the group. In previous work, also supported by FAPESP, the researchers showed how a greater diversity of native species works as a way to contain invasive grasses (read more at: agencia.fapesp.br/51061).

In the case of acidification, the researchers point out that iron sulfate is only one of the compounds that can perform this function. Experiments in the northern hemisphere, for example, have used sulfur for the same purpose. But to do anything on a large scale in the future, the best cost-benefit ratio must first be determined.

“In theory, any acidic substrate could work. One option could be sugar cane processing residue, which is abundant and cheap. On the other hand, discarded chicken litter [sawdust or other material used on farm floors] is quite acidic, but contains a lot of nitrogen, which favors invasives. You have to assess the potential impacts of each option and the financial viability,” says the researcher.

Another factor to consider in future restoration efforts, says Martins, is the soil’s microbial community, which is still poorly understood in the Cerrado.

“Soil microorganisms are the basis of nutrient cycling. For that reason, ways to bring back the original ones of the Cerrado are fundamental to restoring this much-threatened biome,” he concludes.

The article “Soil acidification controls invasive plant species in the restoration of degraded Cerrado grasslands” can be read at: onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/rec.14294.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/54209