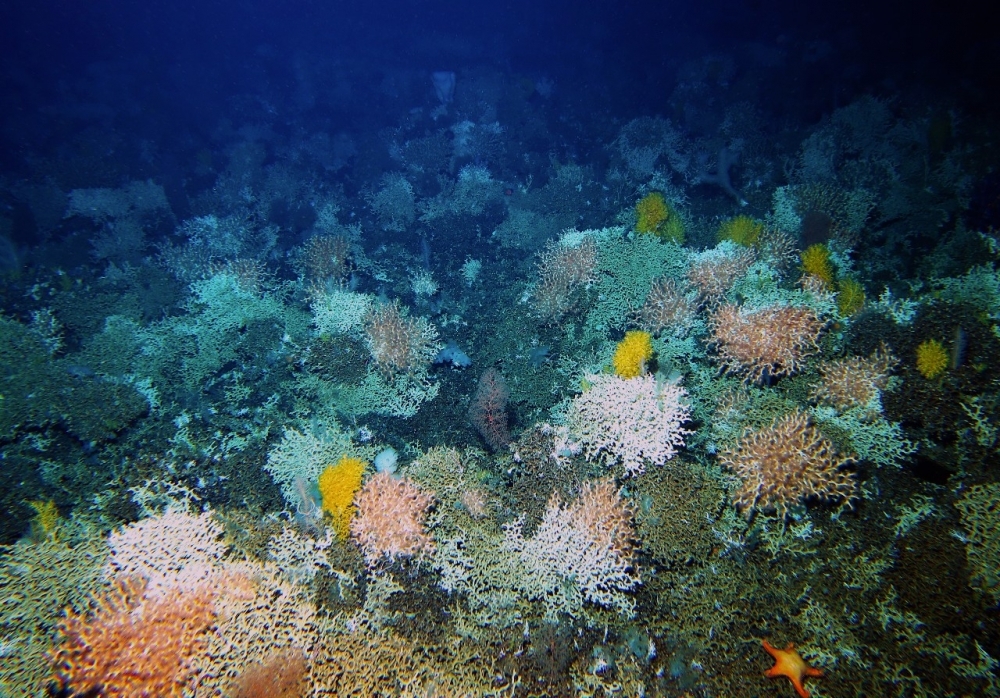

Deep-sea corals normally live at depths of between 200 m and 1,500 m, and do not always form reefs like the one in this photograph. Most are solitary. A book by a Brazilian scientist and an American researcher describes species that live as deep as 3,000 m under the sea in New Caledonia (photo: CSIRO Australia)

Published on 12/13/2021

By André Julião | Agência FAPESP – New Caledonia, an archipelago some 1,200 km east of Australia, has the greatest diversity of deep-sea corals in the world, according to a new book published by France’s National Museum of Natural History, and in which a Brazilian and an American researcher document for the first time 267 species that inhabit the site; 47 are new to science. The book is Volume 32 in the series Tropical Deep-Sea Benthos.

“The region is important to an understanding not just of corals in the Western Pacific, but of this entire animal order, including evolution and how it relates to climate change,” said Marcelo Kitahara, a professor at the Federal University of São Paulo’s Institute of Marine Sciences (IMAR-UNIFESP) in Santos, São Paulo state, Brazil. The other author of the book is Stephen Cairns, a zoologist at the Smithsonian Institution in the United States.

The book presents part of the results of two projects led by Kitahara and funded by FAPESP: “Phylogenomics of the order Scleractinia (Cnidaria, Anthozoa): relationships between evolution and climate change”, and “Deep-sea corals in the South Atlantic: new insights from an interdisciplinary study”.

The findings presented in the book reflect 37 scientific expeditions conducted by the museum between 1978 and 2016. Kitahara took part in several of these, starting while he was researching for a doctorate at James Cook University in Australia, where he analyzed and described some of the specimens collected by the French expeditions. The book covers 53,400 specimens all told.

New Caledonia is a French overseas territory comprising numerous islands and atolls. Its population was a little over 270,000 at the last census. The sea bed is made up of many different types of substrate in a relatively small area (1.1 million sq. km. in the exclusive economic zone). This and the nutrient-rich ocean currents are deemed to explain the outstanding diversity of deep-sea corals, also known as azooxanthellate corals.

The name means lacking in zooxanthellae, a group of microscopic algae that live in symbiosis with coral polyps in shallow water and function like true organs. Because the algae that supply them with nutrients need sunlight for photosynthesis, corals that live near the surface of the ocean have evolved to form large colonies and maximize the capture of light (more at: revistapesquisa.fapesp.br/en/perfect-match/).

Normally found at sunless depths of between 200 m and 1,500 m, azooxanthellate corals have adapted in other ways, such as developing shapes that favor the capture of organic and inorganic nutrients present in the water column. They are also able to tolerate temperatures as low as -1 °C.

Another curious fact about these organisms is that 76% of species are free-living and do not form colonies. Some sightings point to an ability to move on the substrate, enter into and emerge from sand, or even inflate tissue like a balloon to take advantage of the currents.

In addition to the 47 new species they documented, the researchers recorded the occurrence of 200 species known from elsewhere for the first time in the archipelago. They also observed an increase in the greatest known depth for some species believed to live in shallow water to over 3,000 m.

The book Azooxanthellate Scleractinia (Cnidaria, Anthozoa) from New Caledonia, by Marcelo V. Kitahara and Stephen D. Cairns can be purchased at: sciencepress.mnhn.fr/en/collections/memoires-du-museum-national-d-histoire-naturelle/tropical-deep-sea-benthos.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/37564