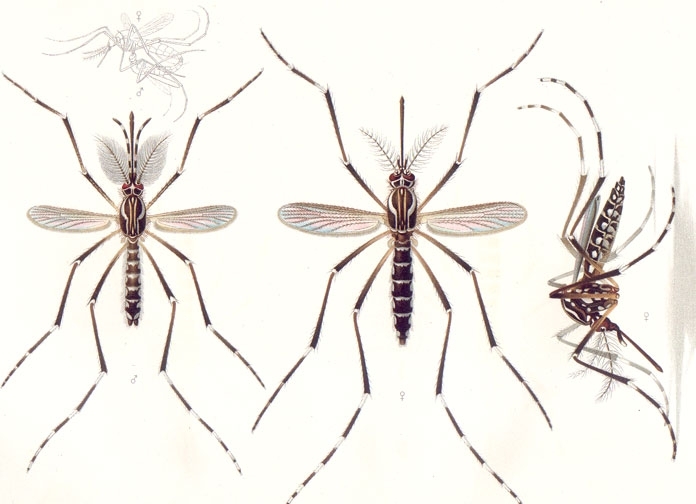

The method identifies and distinguishes between flaviviruses that cause many diseases in humans and animals in Brazil (mosquito Aedes aegypti, a flavivirus vector; image: Emil August Goeldi (1859-1917) / Memórias do Museu Goeldi, Wikimedia Commons)

Published on 03/19/2021

By José Tadeu Arantes | Agência FAPESP – There are more than 70 species of flavivirus, and many cause diseases in humans and animals, including dengue, Zika and yellow fever viruses. A novel flavivirus identification test that is both fast and sensitive has been validated in Brazil by Mariana Sequetin Cunha and collaborators at the Adolfo Lutz Institute, a leading epidemiological surveillance laboratory that reports to the São Paulo state government.

An article on the topic has been published in Archives of Virology.

The research was supported by FAPESP via a Thematic Project, for which the principal investigator (PI) was Maurício Lacerda Nogueira, and a Regular Research Grant for which the PI was Paulo Cesar Maiorka.

“We set out to improve the monitoring of flaviviruses in Brazil by means of a reliable method. To this end, we used the RT-qPCR assay technique,” Sequetin told Agência FAPESP. RT-qPCR stands for reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction. The laboratory technique combines reverse transcription of RNA into DNA and amplification of specific DNA targets using polymerase chain reaction. It is considered the gold standard for rapid identification of viruses and is recommended by the World Health Organization for diagnosing infection by SARS-CoV-2.

“Until recently, the main method used in Brazil to identify flaviviruses required inoculating the brains of newborn mice with suspected material sampled from human patients or animals,” Sequetin said. “When I joined the Adolfo Lutz Institute as a researcher in 2012, I decided to establish an alternative method that would not require the mice but would submit the patient’s blood, serum or viscera sample directly to RT-qPCR.”

The key question was whether RT-qPCR would be sensitive enough to detect small amounts of viruses in the samples analyzed. Sequetin recalled that the Adolfo Lutz Institute maintained a large number of deep-frozen mice that had been inoculated in the 1990s and stored at -80 °C. “I extracted genetic material from their brains and sought the threshold for detection of different flaviviruses by preparing increasingly dilute solutions,” she said.

The protocol established was shown to be highly sensitive and specific. It can be used to detect the different flaviviruses that occur in Brazil and for viral monitoring in sentinel animals and vectors.

“We’re going to test it on new samples that we’re receiving. I expect to find flaviviruses not described in the literature, especially in mosquitos,” Sequetin said.

The article “Applying a pan-flavivirus RT-qPCR assay in Brazilian public health surveillance” can be retrieved from link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00705-020-04680-w.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/33942