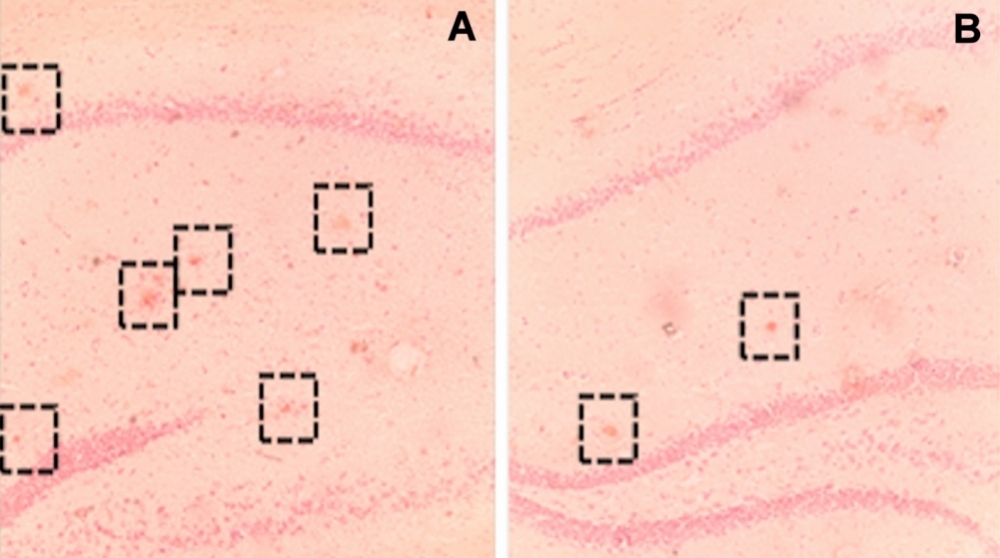

Density of senile plaques in the brains of transgenic mice not exposed to cognitive stimuli (A) and the brains of mice exposed to an enriched environment (B) (image: Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience)

Published on 05/13/2021

By Elton Alisson | Agência FAPESP – Stimulating physical, social and recreational activities in older people and patients with Alzheimer’s disease can help preserve cognitive functions and delay the clinical manifestations of dementia such as memory loss, as recent research has demonstrated. This protective effect is because these activities help build structural and functional reserves in the brain, protecting it from lesions that cause cognitive damage.

A new study supported by FAPESP confirms this hypothesis. The study was performed at the University of São Paulo (USP) and the Santa Casa de São Paulo Medical School (FCMSCSP) in Brazil.

The researchers found that cognitive and physical stimulation of artificially aged transgenic mice in a model designed to mimic late-onset Alzheimer’s disease protected their brains against senile plaque deposition and improved their spatial memory. The study is described in a paper published in the journal Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience.

“We observed that stimulation was sufficient to interrupt the formation of senile plaques and promote a moderate improvement in the animals’ spatial memory,” said Tânia Araújo Viel, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities (EACH-USP) and principal investigator for the project.

A significant amount of evidence gleaned in recent years shows that Alzheimer’s disease is more pronounced in people who have experienced fewer cognitive, social and physical stimuli during their lives, Viel told Agência FAPESP. Environmental stimulation promotes morphological and functional changes in the brain that contribute to the construction of a cognitive reserve.

In this study, the researchers evaluated the effects of enriched environmental stimulation on spatial memory and senile plaque formation in transgenic mice of an advanced age (more than 8 months) that overexpressed a mutant form of human beta-amyloid precursor protein.

Overexpression of this peptide causes an increase in senile plaque deposition in the brain, which is one of the main pathological characteristics of Alzheimer’s disease. “Increased cerebral beta-amyloid load is thought to precede the onset of the disease by approximately 20 years,” Viel said.

The researchers placed transgenic mice and another group of wild-type mice that did not overexpress the beta-amyloid precursor protein in cages with physical and cognitive stimuli of different kinds.

The enriched environment in each cage comprised randomly chosen objects, including ladders, exercise wheels and balls of various sizes, and with different colors and textures. The objects were changed every two to three days. Two other age-matched groups of transgenic and wild-type mice were placed in cages without an enriched environment.

The animals were kept in the respective environments from ages 8 months to 12 months, when they began exhibiting the senile plaques characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. After this four-month period, the mice were submitted to a spatial memory test, and their motor activity was analyzed using sensors. Spatial memory was assessed using a Barnes maze test to measure the time taken by an animal (after a five-day learning phase) to find the exit from an arena with 30 radially arranged holes, only one of which led to the escape box.

The results of the tests showed that the transgenic mice exposed to the enriched environment took 24.5% less time to enter the escape box a week after the learning phase than the transgenic mice that received no stimulus. “This suggests a moderate improvement in spatial memory,” Viel said.

The researchers also analyzed samples of brain tissue from the mice in each group. They found 69.2% lower senile plaque density in the transgenic mice exposed to the enriched environment.

The researchers also found a moderately increased level of a scavenger receptor expressed in microglia that mediates the clearance of beta-amyloid peptides in the enriched environment-exposed group. Microglia are the resident immune cells of the central nervous system.

The reduction in senile plaque density was most conspicuous in the dorsal region of the hippocampus, which is associated with spatial memory, the authors note.

“Stimulation of old mice by an enriched environment for four months led to the formation of a cognitive reserve that protected their brains against senile plaque deposition, and this promoted an improvement in spatial memory,” Viel said.

Dogs and humans

According to the researchers, the study shows that cognitive, physical and social stimulation can complement current pharmacological approaches to the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

The stimuli in question can alter brain metabolism, reduce neuroinflammation, mitigate astrocyte reactivity, and protect the brain against amyloid peptide buildup and senile plaque formation. Astrocytes are the most abundant cells of the central nervous system.

While not immediate, these benefits can be observed in the long run, note the authors of the paper.

“The study proves that positive lifestyle changes can enhance brain plasticity and contribute to the construction of a cognitive reserve during aging, for example,” Viel said.

Viel is currently doing a research internship at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging in California (USA) with a scholarship from FAPESP.

During the internship, she studied the action of microdose lithium on human astrocytes derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), a rising technology with the potential to promote personalized medicine by enhancing the effects of pharmacological treatment and mitigating side effects.

“Lifestyle changes also include the use of ‘neutraceuticals’ [fortified foods that not only supplement diet but also assist in treating or preventing disease] to build up a cognitive reserve in a similar strategy to environmental enrichment,” Viel said.

The researchers have also conducted comparative studies using blood samples from young and old dogs to determine whether differences in cerebral biomarkers can be detected.

The next experiment they plan to perform will investigate whether an enriched environment also alters the blood markers associated with memory in dogs and humans and, by extension, whether differences in the cerebral and blood biomarkers they observed in mice are also found in dogs and humans.

“We already have some evidence that they are, but we’re currently engaged in a survey of several biological markers to confirm the hypothesis,” Viel said.

The choice of domestic dogs as a model for this type of study is because they tend to have a similar lifestyle to their owners. If a dog owner is physically active, the dog also tends to be physically active, according to recent research.

“We want to see if there’s a difference in terms of cognitive biomarkers between physically active animals and others that live sedentary lives shut up in houses or apartments,” Viel said.

The article “Enriched environment significantly reduced senile plaques in a transgenic mice model of Alzheimer’s disease, improving memory” (doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00288) by Janaina Balthazar, Natalia Mendes Schöwe, Gabriela Cabett Cipolli, Hudson Sousa Buck and Tânia Araujo Viel can be read in Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience at www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2018.00288/full.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/29927