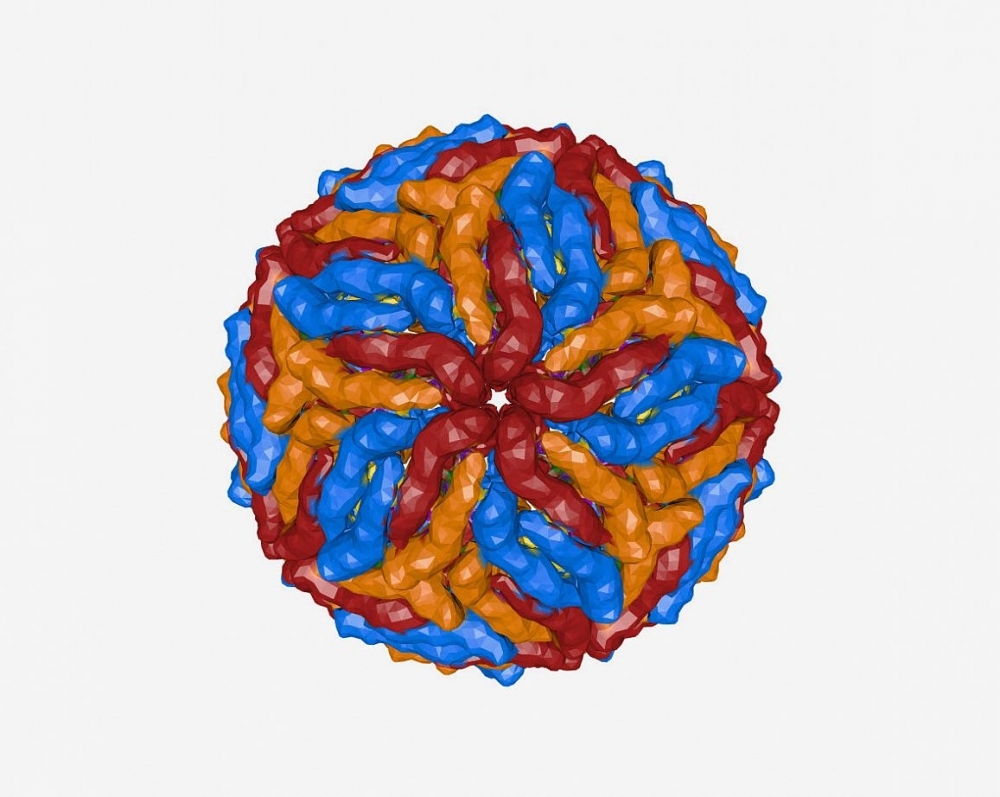

A study by Brazilian researchers evidenced a correlation between post-zika neurological complications and high levels of Gas6, a protein that facilitates viral replication. The findings are published in Brain, Behavior, and Immunity (3D model of zika virus; image: NIH)

Published on 09/27/2021

By Luciana Constantino | Agência FAPESP – An article by Brazilian researchers published in the journal Brain, Behavior, and Immunity elucidates one of the mechanisms whereby zika virus causes neurological complications in adult patients and microcephaly in fetuses. The discovery paves the way for future research to develop drugs that combat the virus.

In the study, which was supported by FAPESP, the researchers found a correlation between the neurological complications caused by zika and high levels of Gas6, a protein that helps the virus invade human cells. They also showed that the main source of Gas6 in such cases is peripheral monocytes, a type of white blood cell that plays a key role in the immune system’s ability to destroy invaders, as well as facilitating healing and repair.

In its active form, Gas6 binds to receptors in the TAM family (Tyro3, Axl and Mer) and, after entering the cell, suppresses the organism’s inflammatory response, facilitating viral replication and aggravating the infection.

“The virus itself triggers expression of Gas6, which is augmented in patients with the severe form of the disease. High levels of the protein are associated with an increase in suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 [SOCS-1], a potent inhibitor of type 1 interferon (IFN1). The more potent the mechanism, the worse the prognosis,” said José Luiz Proença Modena, a professor at the University of Campinas’s Institute of Biology (IB-UNICAMP) and last author of the article. IFN1 is an important part of the immune response against viruses and other pathogens.

Three groups participated in the study. Modena’s group analyzed blood serum samples from zika patients, including pregnant women. A second group was led by Fábio Trindade Maranhão Costa, also a professor at IB-UNICAMP. Animal trials were conducted by a third group, which was led by Jean Pierre Schatzmann Peron, a professor in the Department of Immunology at the University of São Paulo’s Biomedical Sciences Institute (ICB-USP) and a member of the Scientific Platform Pasteur-USP (SPPU), part of the Institut Pasteur International Network.

Some of the researchers belong to UNICAMP’s Zika Network, established in 2016 after the zika epidemic in Brazil to conduct research that helps deal with the severe impact on public health of the diseases transmitted by the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Singapore’s A*STAR Infectious Diseases Labs also collaborated on the study. The partnership has resulted in other publications, including an article on a study that identified a marker for zika.

“Our Zika Network was a precursor of similar collaborations, which continue to take shape and grow,” Costa said. “They bring together competent professionals and complementary research lines, combining expertise and know-how. The results are very positive, with collaboration contributing to the quality of the work.”

Zika became a public health problem in 2015, starting in South America and spreading to more than 94 countries. It was first detected in 1947 in Uganda (East Africa) but was not considered a human health hazard until the 2015-16 outbreaks.

Some 214,000 probable cases were notified in Brazil in 2016, followed by 17,000 in 2017 and 8,000 in 2018. According to the Ministry of Health, 2,006 probable cases were notified in January-May 2021.

The rise in cases of zika was accompanied by an increase in cases of microcephaly, a rare neurological disorder in which the fetal or newborn’s brain fails to develop completely. More than 2,400 cases of microcephaly were notified in Brazil in 2015, compared with 781 in the previous five years.

The zika epidemic in Brazil occurred in areas historically endemic for dengue. Both are flaviviruses transmitted by A. aegypti and cause similar symptoms (high fever, rash, headache, red eyes and joint pain).

Although zika is usually asymptomatic, recent data shows a link between the disease and the development of neurological complications such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, encephalitis and meningitis in adults, and congenital malformations such as microcephaly in infants. The virus has been shown to be able to cross the blood-brain barrier and also to enter the placenta, where it infects the fetus.

According to Modena, there was already plenty of evidence in the literature that dengue virus can interact with Gas6 and use this mechanism to penetrate phagocytes and replicate. This has now been demonstrated for zika as well.

Understanding the path

To find out how Gas6 levels correlated with the neurological complications associated with zika, the researchers used the ELISA enzyme-linked immunoassay to analyze serum samples from patients included in a cross-sectional study conducted between February 2016 and June 2017 in hospitals in Campinas, state of São Paulo.

Ninety patients and 13 healthy controls were enrolled in the study: 57 patients had mild self-limited zika and were labeled “non-neuro”, while 19 had neurological complications after being infected by zika (“neuro”), and 14 had neurological complications without having zika (“neuro non-zika”). The “neuro” group had higher levels of Gas6 and SOCS-1.

Meanwhile, Peron and colleagues were working with adult mice bred at the university to be immunocompetent, i.e. with an immune system capable of combating the virus (C57BL/6 and SJL mice). “We inoculated the virus with and without Gas6 into pregnant and non-pregnant mice. Viral load on the first day after infection was much higher in the adult mice that received the virus with Gas6, showing that the protein favors infection. A high proportion of their offspring had congenital malformations, with smaller heads and lower overall size,” said Lilian Gomes de Oliveira, joint first author of the article with João Luiz da Silva Filho.

In order to invade monocytes by binding to cell receptors, Gas6 must undergo carboxylation, a chemical reaction that enables it to interact with other molecules. The researchers tested in vitro the use of a drug that inhibits carboxylation (warfarin), which did indeed block or reduce viral replication.

“By deciphering this mechanism, we’ve opened up the possibility of further research that could serve as a basis for intervention with drugs. We showed that treatment of cultured cells with warfarin was effective to inhibit multiplication of the virus. We didn’t conduct a clinical trial, but the door is open,” Modena said.

For Peron, the findings contribute to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of severe zika and its outcomes and point in the direction of studies in pursuit of ways to use Gas6 as a therapeutic tool. Currently, he leads a project, also supported by FAPESP, focusing on the immunopathogenesis of COVID-19 in experimental models.

The article has a total of 46 authors and received support from FAPESP via several projects (16/00194-8; 17/26170-0, 16/12855-9, 16/21259-0, 18/13866-0, 17/02402-0, 16/07371-2, 17/11828-0, 17/26908-0, 17/22062-9, 18/13645-3, 20/02159-0, 17/22504-1, and 20/02448- 2).

The article “Gas6 drives Zika virus-induced neurological complications in humans and congenital syndrome in immunocompetent mice” can be retrieved from: www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0889159121002981.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/36943