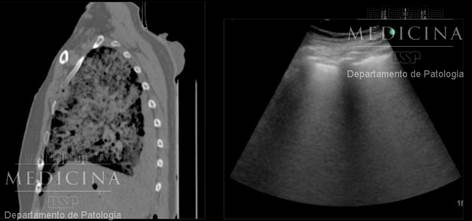

Chest scan showing signs of viral pneumonia (white patches or ground glass opacities) (image: Department of Pathology, FM-USP)

Published on 03/25/2021

By Elton Alisson | Agência FAPESP – Researchers affiliated with the University of São Paulo’s Medical School (FM-USP) in Brazil are using a minimally invasive procedure to perform autopsies on the bodies of patients who are diagnosed with COVID-19 and die at the institution’s teaching hospital (Hospital das Clínicas).

One of their aims is to collect tissue samples from lungs and other organs, analyze them quickly and publish their findings to help physicians and other health workers treat severe cases of the disease.

“We’re sharing the preliminary results of the analyses with the medical team at Hospital das Clínicas and other institutions even before we publish them in scientific journals, because we expect the findings to contribute to decisions on the treatment of patients who are in hospital now,” Marisa Dolhnikoff, a professor at FM-USP, told Agência FAPESP. Dolhnikoff is principal investigator for the study, which is part of a project supported by FAPESP.

The researchers plan to correlate CT scans of deceased patients’ lungs and other organs with the clinical observations made by medical staff while the patients were undergoing treatment in an intensive care unit (ICU). The idea is to see whether patients hospitalized for relatively long periods display other alterations to their lungs, and whether the different forms of mechanical ventilation used in ICUs cause different alterations to the lungs.

“This correlation represents a key step in the study because there may be different tomographic, pathologic and clinical profiles of COVID-19,” Dolhnikoff said.

“When we started making the data available, we were immediately contacted by clinicians to tell us that the patient CT scans they’re analyzing in hospitals aren’t all the same. This raised the question whether the disease’s patterns of pulmonary behavior may vary.”

Six autopsies of patients who died from COVID-19 were performed in the state of São Paulo with their families’ consent until the week beginning March 30. The plan is to perform 20-30 autopsies using a minimally invasive technique: a portable ultrasound device equipped with a biopsy needle scans internal organs and collects tissue samples, so that there is no need to cut the body open (read more at agencia.fapesp.br/32810).

The first four patients analyzed were two men and a woman, all over 60 and with a history of chronic diseases such as diabetes and high blood pressure, and a younger patient also with pre-existing diseases. They all died quickly of COVID-19, within four to ten days.

The preliminary results of the analyses pointed to similar alterations to those described by Chinese researchers in four articles published in recent weeks, reporting on autopsies of several deceased patients diagnosed with COVID-19.

“The Brazilian medical community is deeply interested in the data we’re producing because it may provide more immediate answers to questions such as precisely how the virus affects the lungs,” Dolhnikoff said.

Multiple extensive lesions

The analyses performed by the FM-USP group corroborated the finding that death from COVID-19 is due to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), with widespread inflammation and extensive severe lesions caused by SARS-CoV-2 in multiple areas of the lungs.

The virus mainly infects the epithelial cells that line the pulmonary alveoli, participating in the exchange of carbon dioxide for oxygen. Loss of these epithelial cells causes extensive lesions in the alveoli (tiny sacs in which the gas exchange occurs). Known as diffuse alveolar damage, these lesions impair gas exchange in a large portion of the lung, reducing tissue oxygenation and leading to respiratory failure.

“We found that the virus infects the entire respiratory tract but causes the most damage to alveoli,” Dolhnikoff said.

In severe cases of COVID-19 the lesions are very similar to those observed in cases of SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), both caused by other coronaviruses.

“Analysis of the CT scans showed us that some regions of the lung are more affected, such as the posterior portion, and that the infection damages at least half of the lung,” Dolhnikoff said.

In one of the cases the researchers also observed small foci of bleeding in the pulmonary microcirculation, associated with microthrombi.

“This phenomenon is certainly associated with the coagulation disturbances described in patients who die from COVID-19,” Dolhnikoff said.

Bacterial pneumonia

Another question the researchers plan to try to answer by correlating the results of tissue analysis with clinical data and CT scans is whether the secondary bacterial pneumonia seen in critical patients as a clinical complication is linked to the length of time during which they undergo mechanical ventilation.

Analysis of the first four cases showed that two patients had severe bacterial pneumonia after the viral infection. This information was immediately given to the medical teams.

“A viral infection often leads to bacterial pneumonia, but treatment of these severe cases requires rapid identification of bacterial infection and treatment with antibiotics,” Dolhnikoff said.

When viral and bacterial pneumonias occur concomitantly, serious damage can be done to the lungs and the entire organism, as the pathogens circulate and injure other organs.

“The bacterial infection has a huge impact on pulmonary function and affects other organs, potentially resulting in sepsis [multiple organ failure] and death,” Dolhnikoff said.

So far the researchers have not observed acute alterations to other organs caused by the virus. The alterations identified were associated with sepsis or pre-existing conditions such as chronic kidney and heart disease, hypertension and ischemia, and fatty liver disease (hepatic steatosis) associated with diabetes and obesity.

Because data from the medical literature suggests infection by the novel coronavirus is not limited to the lungs, with evidence that it is excreted in feces and urine, and also that it causes loss of smell and taste, the researchers plan to investigate its effects on other organs by analyzing samples of tissue from the heart, kidneys, liver, spleen, brain, bone marrow, skeletal muscle, and nasal and oral mucosa.

“We also want to create a biorepository of tissue samples that can be studied using advanced molecular biology techniques to identify possible therapeutic targets to combat the disease,” said Paulo Saldiva, a professor at FM-USP and one of the researchers who are participating in the project.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/32955