Old-growth area of Cerrado in Chapada dos Veadeiros National Park, Goiás state (photo: Natashi Pilon/UNICAMP)

Published on 07/29/2024

By José Tadeu Arantes | Agência FAPESP – The Cerrado has lost some 70% of its original plant cover. Despite being the world’s most biodiverse savanna, with 33% of Brazil’s biodiversity, and the source of South America’s three greatest rivers, the Cerrado is also Brazil’s most endangered biome. Saving what remains by means of conservation actions is necessary and urgent. It is not sufficient, however. Restoration is also needed.

The problem is that the Cerrado is very hard to restore. In recent decades, various restoration methods have been tested, but none has proven entirely effective. To understand the potential of each approach and find out whether they can be combined into a single strategy, a study supported by FAPESP compiled a large dataset for 82 different areas located in five states and the Federal District. An article on the study is published in the Journal of Applied Ecology.

“We compared the areas to see how similar those undergoing restoration were to well-conserved old-growth areas, and how much the physiognomies of open fields and savannas that predominate in the biome were recreated. In each area, we assessed the efficacy of passive restoration [involving natural regeneration or rewilding] and active restoration [seeding, tree planting, and transplantation of plants, roots and soil],” said Natashi Pilon, first author of the article and a professor at the State University of Campinas’s Institute of Biology (IB-UNICAMP) in São Paulo state, Brazil.

The study investigated 712 species typical of old-growth Cerrado. Almost half (338, or 47%) were not found in any of the areas undergoing restoration. Worse still, 70% of 520 species detected only in areas undergoing restoration were not typical of the Cerrado. In other words, species that should have been present in restored areas were not found there, and species that should not have been were.

“Species that aren’t characteristic of the Cerrado are being introduced in the restoration projects. Examples include ruderal plants [the first to colonize disturbed land]. The species involved are native to Brazil, but they aren’t characteristic of any particular biome, and in the long term they compromise the stability of the ecosystem that’s being restored,” Pilon said.

The limits of natural regeneration

The Cerrado is highly diversified. One of the aims of the study was to understand how each type of plant responds to different restoration techniques, considering native grasses, forbs (herbaceous flowering plants other than grasses), subshrubs (plants with woody stems at the base but herbaceous or non-woody stems and leaves above ground), shrubs, climbers and trees.

“We found that the number of typical species didn’t increase over time in areas allowed to regenerate naturally, showing that many species have a limited ability to colonize degraded areas and that simply letting the Cerrado regenerate on its own won’t recover lost biodiversity,” Pilon said.

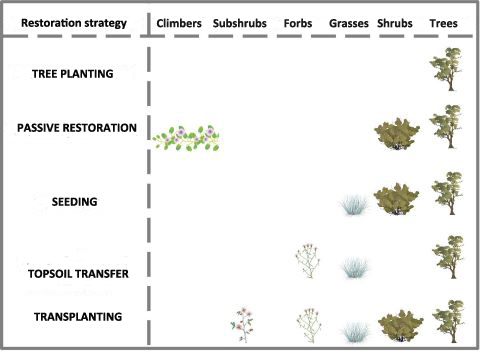

Figure 2 below, derived from the study, illustrates the efficacy of each restoration technique for the various plant types. As can be seen, passive restoration permits conservation of a limited number of typical species, mainly trees and shrubs with high resprouting capacity. Even so, recovery by these woody species depends on the extent to which the soil has been modified and whether roots capable of resprouting still exist. As for active restoration techniques, the figure shows that seeding and transplanting plants and soil can restore a greater diversity of typical species, each technique being favorable for a specific type of plant.

Main Cerrado plant types and restoration techniques (image: Natashi Pilon/UNICAMP)

“Every component of these complex ecosystems plays an important role in their resilience and functioning. Effective restoration must therefore consider all these factors. For example, native grasses fuel the wildfires that control the density of woody species. This is a natural process in savanna-like ecosystems. The diversity of forb species regulates pollinator dynamics, keeping their populations in the landscape and providing resources for bees to forage throughout the year. Subshrubs and shrubs resprout and quickly colonize the area after natural disturbances and are highly resilient to anthropogenic disturbances. They also store large amounts of carbon underground in their well-developed subterranean structures. Successful restoration aimed at recovering biodiversity and/or ecosystem services should therefore consider reintroducing all plant forms found in old-growth areas of the Cerrado,” Pilon said.

Considering the different active restoration techniques and plant types, the study showed that direct seeding, topsoil transposition and plant material transplanting were effective in bringing back native grasses to 18%, the proportion found in old-growth parts of the biome. For typical forbs, proportions similar to this (18%) were obtained by transposing topsoil or transplanting plant material. In areas where restoration mainly involved tree planting, no typical native grasses were observed, and this was the restoration technique with the lowest score of all in terms of efficacy.

For subshrubs, transplanting was the only technique that recovered typical species in proportions close to that found in old-growth ecosystems (24%). In the case of shrubs, the proportion was similar to the reference number (14%) for most of the techniques analyzed. The exceptions were surface soil transposition and tree planting, which led to far lower levels of restoration. The proportion of trees surpassed that of conserved ecosystems in most of the restoration interventions analyzed.

“Based on these results, we conclude that there is no panacea for effective restoration of the Cerrado. No technique alone can bring back all the components needed to guarantee the biome’s resilience and functioning. Furthermore, the techniques with the best results – seeding and transplanting – are highly dependent on old-growth areas for acquisition of seeds and entire plants with roots. Policies and strategies that promote conservation are therefore just as urgent as restoration, if not more so,” Pilon said.

“When people talk about the Amazon Rainforest, their focus is on conservation. But in the case of the Cerrado, it’s on restoration. Our study shows that while restoration is indeed indispensable, it’s not easy. And it depends on conservation. Despite all the destruction, there’s still a lot of Cerrado to conserve, especially in the northern part, in the area known as MaToPiBa [a portmanteau referring to the agricultural frontier made up of parts of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia states]. The challenge is that this area is being adversely affected by the expansion of agriculture, as happened previously in Goiás and Mato Grosso.”

The study collected data from this area as well as other parts of the Cerrado. The field survey was conducted on private properties and several conservation units, such as Santa Bárbara Ecological Station, Assis State Forest, Itirapina Ecological and Experiment Station and Itararé Research and Development Unit in São Paulo; Chapada dos Veadeiros National Park and Emas National Park in Goiás; Pombo Municipal Park in Mato Grosso do Sul; and Guartelá State Park in Paraná. The study was supported by FAPESP via three projects (19/07773-1, 20/09257-8 and 19/03463-8).

The article “Challenges and directions for open ecosystems biodiversity restoration: an overview of the techniques applied to the Cerrado” is at: besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2664.14368.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/52330