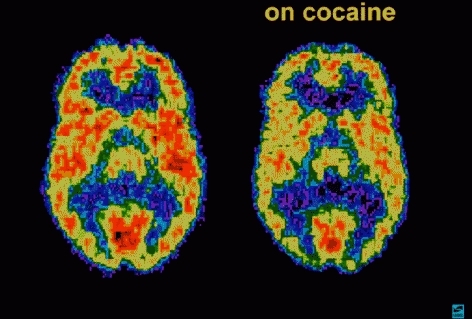

Brazilian researchers combined cognitive dysfunction tests with an analysis of drug use patterns to identify patients at high risk of relapse after treatment (image: positron-emission tomography (PET) showing how cocaine alters glucose metabolism in the brain / National Institute on Drug Abuse)

Published on 05/13/2021

By Karina Toledo | Agência FAPESP – A study conducted at the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil and described in an article published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence may help healthcare workers identify patients who risk relapse after undergoing treatment for cocaine use disorder.

According to the authors, the findings reinforce the need to offer individualized treatment strategies for these cases, which are considered severe.

The principal investigator for the study was Paulo Jannuzzi Cunha, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s Medical School (FM-USP), with a postdoctoral research scholarship from FAPESP and support from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

For 30 days, the researchers monitored 68 patients admitted for treatment for cocaine dependence to the Psychiatry Institute of Hospital das Clínicas, FM-USP’s general and teaching hospital in São Paulo. All patients volunteered to participate in the study. They were contacted three months after discharge to verify their abstinence. All but 14 reported a relapse, defined as at least one episode of cocaine use during the period.

One of the goals of the study was to determine whether the 11 criteria for diagnosing chemical dependence established in the DSM-5 were also effective at predicting the response to treatment. DSM-5 is the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and valued as the standard classification by mental health professionals in many parts of the world.

“Our hypothesis was that these criteria would not help accurately predict relapse. However, after completing the study, we recognized that they may in fact be useful for predicting vulnerability to relapse,” Cunha told Agência FAPESP.

The DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing a substance use disorder include taking the drug in larger amounts and/or for longer periods than intended; craving, or a strong desire to use the drug; giving up social, occupational or recreational activities because of substance use; continued use despite having persistent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of the drug; tolerance (needing increasing amounts to achieve the desired effect); and withdrawal symptoms, among others.

According to the DSM-5 guidelines, a substance use disorder can be considered mild if two or three of the 11 criteria are met for a year, moderate if four or five are met for a year, or severe if six or more are met for a year.

“Our sample included only cases classified as severe. We observed a clear difference between patients who met six to eight criteria and those who met nine to 11. The relapse rate was significantly higher in the latter group,” said Danielle Ruiz Lima, first author of the article.

The results suggested that the three categories recommended by DSM-5 should be reviewed. “There seems to be an ‘ultra-severe’ group as well as a ‘severe’ group,” they said.

Refining the analysis

Another hypothesis investigated was that the pattern of cocaine use (DSM-5 score plus factors such as age at use onset and intensity of use in the month prior to hospital admission) and the cognitive deficit caused by the drug were related variables that could help predict a relapse after treatment.

The researchers used several tests to assess the participants’ performance in executive functioning, which include working memory (required for specific actions, such as those of a waiter who has to associate orders with customers and deliver them correctly), sustained attention (the ability to focus for as long as it takes to complete a specific task, such as filling out a form, without being distracted), and inhibitory control (the capacity to control impulses).

The researchers applied the tests a week after admission on average, as they considered this waiting time sufficient to know whether the urine toxicology was negative. The aim of this procedure was to avoid acute effects of the drug on the organism.

One of the tests used to measure memory span required the patient to repeat an ascending sequence of numbers presented by the researchers. Patients who had made intensive use of cocaine in the previous month before admission underperformed on this test.

In other tests, in this case used to measure selective attention, cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control, patients were asked to repeat a sequence of colors and then to name the ink color when the name of a different color is printed (the word “yellow” printed in blue ink, for example).

“The automatic response is to read what’s written instead of naming the ink color, as required. Inhibitory control is essential to perform this task. This function is extremely important in the early stages of drug dependence rehabilitation, when the patient has to deal with craving and situations that stimulate the desire to use the drug,” Cunha said.

The analysis showed a correlation between inhibitory control test results and the age at cocaine use onset. “The earlier the onset, the more mistakes they made, which could point to a higher risk of relapse. The idea is to identify the people who have substantial difficulties so that we can work out individualized treatment strategies,” Lima said.

Intense cocaine use in the 30 days preceding admission also correlated with underperformance on the inhibitory control test and the working memory test, in which the patient was asked to listen to a sequence of numbers and repeat them in reverse order, reflecting an important function for the manipulation of information as a basis for decision making.

According to the researchers, studies have shown that executive functions may be restored after a period of abstinence, but to what extent and how long this recovery may take are unknown.

The research group at FM-USP advocates cognitive rehabilitation programs to support the recovery process. “We have a motivational chess proposal that’s being studied right now,” Cunha said. “A therapist plays chess with the patient and then discusses the moves, making analogies with the patient’s life in an attempt to transfer the knowledge acquired in the chess game to day-to-day experience and train inhibitory control, planning and healthy decision making in the real world.”

In his view, the assessment of cognitive deficits is important for both diagnosing substance use disorder and predicting relapse. “Chemical dependence is a brain disease, and these neuropsychological tests offer a slide rule with which to measure objectively whether the damage is mild, moderate or severe, along similar lines to the classification of dementia,” he said.

According to the researchers, despite the clinical relevance of neuropsychological test results, they are not part of the DSM-5 criteria, which are based solely on self-reported factors and clinical observations.

“We hope the sixth edition of the DSM takes these developments into account in recognition of the research done by us and other groups worldwide,” Cunha said.

The article “The role of neurocognitive functioning, substance use variables and the DSM-5 severity scale in cocaine relapse: A prospective study” by Danielle Ruiz Lima et al. can be retrieved from: www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0376871618306276.

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/30526