Results suggest that intermittent fasting is not recommended for individuals with a family history of bowel cancer (image by pvproductions on Freepik)

Published on 08/04/2025

By Maria Fernanda Ziegler | Agência FAPESP – Intermittent fasting and calorie restriction are touted as beneficial for health and longevity. However, animal experiments published in the journal Nature suggest that depending on what is eaten immediately after fasting and the individual’s genetic predisposition, the practice may increase the risk of developing intestinal tumors.

The study, conducted by scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the United States, is the first to analyze changes in intestinal cells not only during food interruption, but also in the post-fasting period. The researchers found that refeeding triggers an intense proliferation of intestinal stem cells, which can have both beneficial and risky effects on the body, including increased susceptibility to tumor development.

“Does this mean that intermittent fasting causes cancer in the intestine? No. Several studies have already demonstrated the benefits of this practice, including for disease prevention. We found in our study that, by increasing the proliferation of stem cells in the intestine, depending on genetic predisposition and, possibly, what is eaten after fasting, there may be an increased risk of developing tumors just through fasting,” says Renan Oliveira Corrêa, co-author of the article. He participated in the investigation during a research internship at MIT with support from FAPESP.

The results suggest that intermittent fasting is therefore not recommended for individuals with a family history of bowel cancer. The finding also sheds light on what to eat after fasting. Carcinogenic foods, such as processed meat, sugar-rich products, and alcoholic beverages, are not recommended as they could influence the occurrence of genetic mutations during this critical period of cell proliferation.

“Although the experiment was done on mice under artificial conditions, it’s possible to suggest greater caution when practicing intermittent fasting,” says Corrêa, emphasizing that more studies on the subject need to be conducted.

Renewal

As the researcher explains, the epithelium, the tissue that lines the intestine, renews itself at a very high rate. In humans, for example, the epithelium is completely renewed every three to five days. This process occurs naturally through stem cells, which multiply and differentiate to generate all the cell types present in the epithelium.

Recently, researchers have discovered that stem cell proliferation can be influenced by various factors. Previously, Corrêa’s group at the Institute of Biology of the State University of Campinas (IB-UNICAMP) in Brazil showed that diet, specifically the consumption of soluble fiber, promotes epithelial renewal (read more at: agencia.fapesp.br/41957).

“In addition to regulation by ingested nutrients, we’ve now been able to demonstrate that this proliferation can also be modulated by feeding frequency, as in the case of the post-fasting period,” explains Marco Aurélio Ramirez Vinolo, a professor at IB-UNICAMP and co-author of both studies.

“This happens because cells adapt to the condition of food interruption and respond by proliferating more intensely when the animals are fed again after fasting. This has a positive aspect, as it causes the epithelium to maintain itself and recover [from damage or stress, for example] more quickly. However, we’ve identified a potential risk of developing more tumors if cancerous mutations occur at this exact moment of increased proliferation,” points out Vinolo, who was Corrêa’s advisor during his Ph.D.

In the study recently published in Nature, the researchers analyzed stem cell proliferation in three different situations: when the animals were fasting, when they were fed after fasting, and when they were on a normal diet without prolonged breaks from eating. Their comparison revealed that epithelial stem cells proliferate more intensely during the refeeding period (after 24 hours of fasting).

“By analyzing the mechanism involved, we found that the more intense proliferation of stem cells occurs because of the activation of a cellular pathway called mTORC, which is associated with cellular metabolism and protein synthesis. Basically, with the activation of this pathway, more proteins are produced through the metabolism of polyamines, molecules that are important for cell division, which results in greater stem cell proliferation during this refeeding period,” explains Corrêa.

In the study, the researchers found that activating genetic mutations during the post-fasting period increased the likelihood of early-stage intestinal tumor development in mice.

“Our findings therefore show that it’s a case of not pushing one’s luck. Intermittent fasting can be very effective because it actually reduces calorie consumption. Some research has shown that, besides promoting weight loss, the practice reduces the risk of diabetes and can improve the immune system, protecting the body against some types of cancer. However, we’ve identified that it shouldn’t be recommended for everyone, since the refeeding period is a time of high cell proliferation and can make cells more susceptible to tumor formation,” points out Corrêa.

The article “Short-term post-fast refeeding enhances intestinal stemness via polyamines” can be read at www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07840-z.

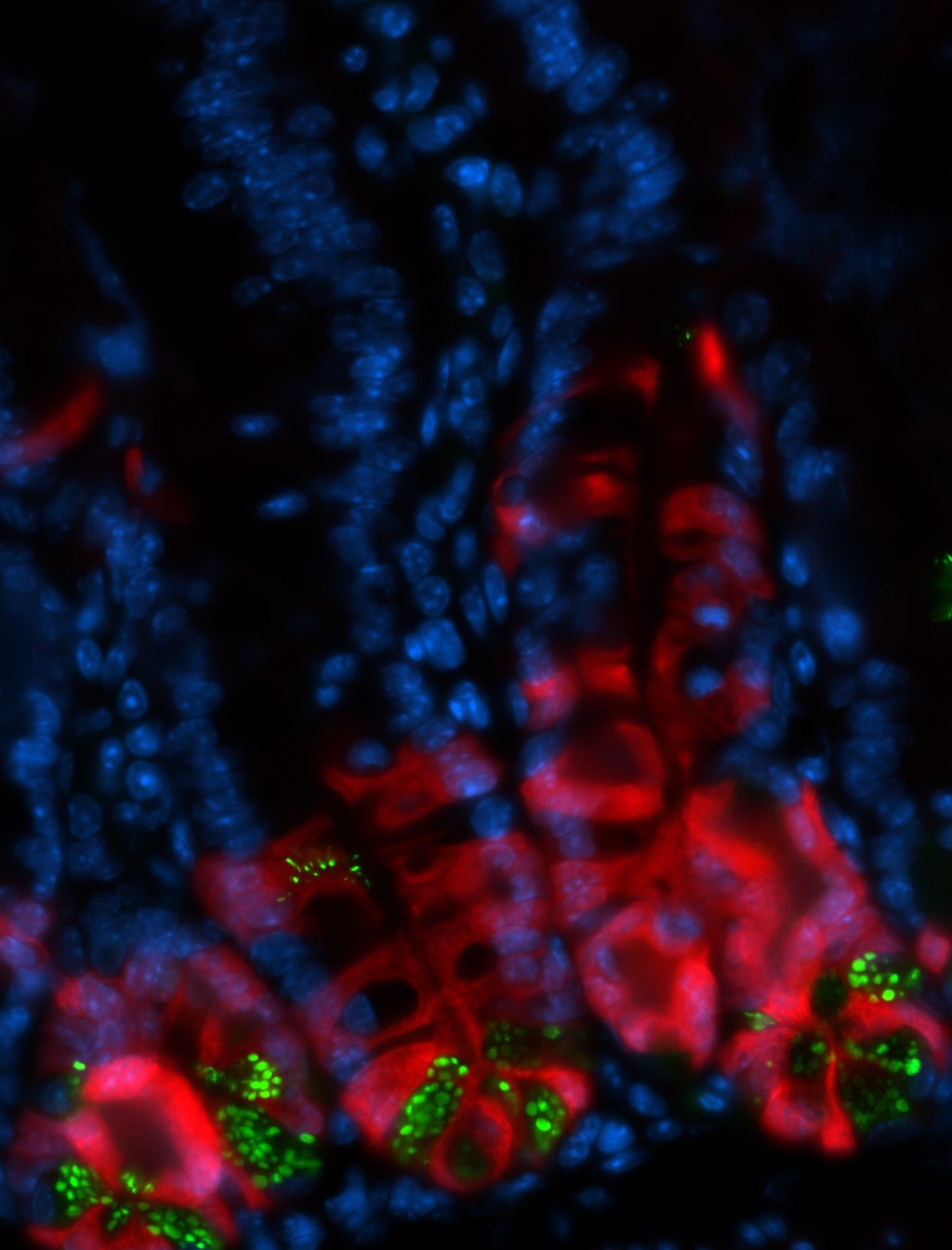

Histological analysis of the intestinal epithelium used to quantify stem cell activity under different feeding conditions. In red are stem cells and progenitor cells (generated by stem cells) after the administration of a specific reagent in mice. A higher number of red cells indicates a higher stem cell proliferation rate. In green are Paneth cells, which perform auxiliary and protective functions for stem cells (image: Renan Corrêa)

Source: https://agencia.fapesp.br/55508